Financial stability review

27 November 2020

Blog

Yesterday, we published our latest Financial Stability Review (FSR), which sets out our views on the most material macro-financial risks facing the Irish economy, our judgments on the resilience of various sectors, along with a number of macroprudential policy announcements. I won’t repeat my statement from yesterday (PDF 244.43KB) but there are a number of points that I’d like to mention.

First, and although obvious, it is worth acknowledging the remarkable uncertainty that has been a feature of 2020. It has dominated the analysis of our economists, supervisors and policymakers and has been the main backdrop for our assessments in this FSR.

Second, the shock has underlined the benefits of building resilience. Households, businesses, the domestic banking system, and the State are stronger than they were through the previous crisis. Yes, government supports have played an important (and necessary) supporting role over the past 8 months but the efforts of the State, households, businesses, the financial system and its regulators since the financial crisis have put us in a stronger position to manage the impact of the pandemic.

Third, we will in due course, of course, have to start rebuilding our resilience.

Fourth, it will take time to see the full effects of the shock on the economy and financial system. Government supports and payment breaks have cushioned the impact on businesses and households but some borrowers are likely to struggle to return to full repayments. As I will discuss further below, the banking system as a whole has loss-absorbing capacity for shocks that are materially worse than current baseline projections. But loss-absorbing capacity is not unlimited either and the outlook beyond the current quarter is characterised by huge uncertainty (the progress of the pandemic, the economic implications of the related public health response and the successful roll-out of a vaccine).

Let me expand on the subject of resilience.

Household resilience

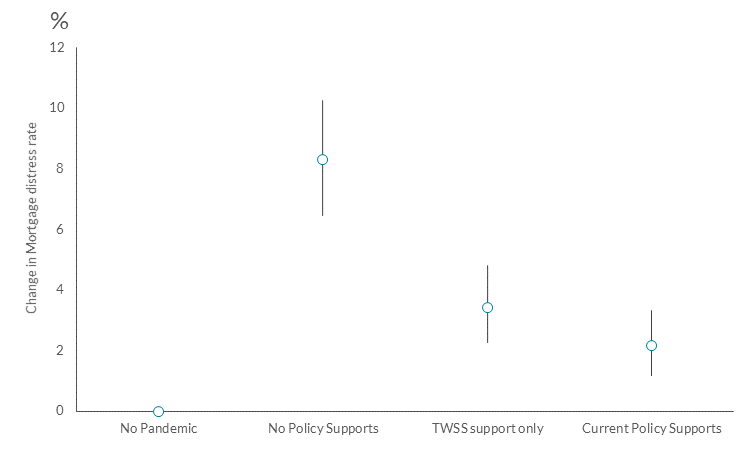

Households are starting from a much better position than the crisis of 2008. State support has cushioned much of the effect of the COVID-19 shock to employment and income, with close to half of all workers relying on the State for some of their income at the peak in June. Figure 1 outlines how important policy supports have been for households. Without them, assuming all those on the TWSS or PUP were to receive Jobseeker’s Benefit, the distress rate on mortgages could have risen to 10 per cent by mid-2021.

Figure 1: Government Supports

Source: Department of Finance Credit Demand Survey

Note: The chart shows modelled change from a baseline mortgage default rate of 4per cent 18 months after the onset of the pandemic. The data series are results from a simulation exercise in which the impact of the pandemic on household incomes is modelled based on available data and known features of the policy supports, in addition to Central Bank forecasts as of June 2020 and modelling assumptions informed by academic research. Each data point is accompanied by a 95 per cent simulation interval which represents a likely range of outcomes based on the modelling assumptions. “No pandemic” shows outcomes when labour income is completely unaffected. “No policy supports” shows outcomes when persons whose labour income is affected by the pandemic receive jobseeker’s benefit. “TWSS support only” shows a policy scenario in which current TWSS recipients are unchanged, but PUP recipients receive jobseeker’s benefit instead. “Current policy supports” shows scenario in which PUP and TWSS programmes are unchanged and homeowners can avail of a six month payment break.

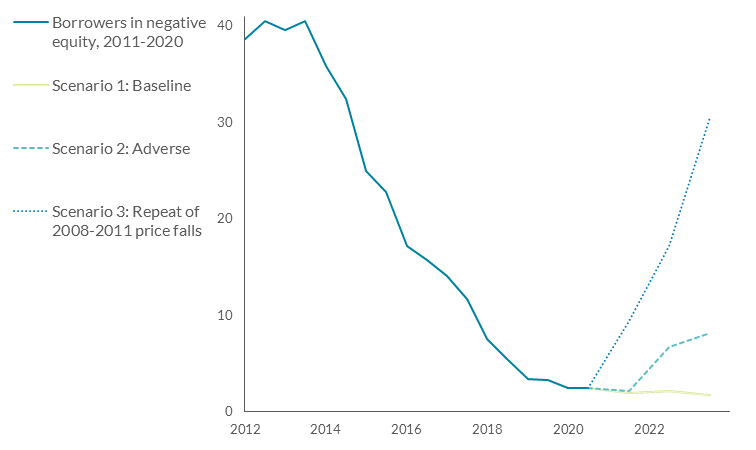

Looking at data from June, before a significant share of payment breaks began to expire, two sources of vulnerability can be disentangled: those relating to COVID-19 payment breaks, and those relating to legacy issues from the previous crisis. Figure 2 shows that under our baseline scenario (which assumes a gradual opening-up and recovery), the proportion of households falling into negative equity will continue to decline. And in our adverse scenario (where house prices fall by about 20% over the 2019-2022 period), negative equity would rise but only to 2018 levels, implying there is significant resilience in the mortgage market to this risk. Government policies have provided income replacement never seen before in Ireland, and this exceptional support will reduce mortgage repayment difficulties.

Figure 2: Negative Equity Risks

Source: Central Bank of Ireland

Notes: Scenario projections are as at 30 June in each year from 2021 to 2023. In each scenario, loans amortise on schedule; however, this plays a relatively small role compared to property price fluctuations. New loans originate each year at 2018 LTVs and volumes.

Banking sector resilience

The FSR also includes a forward-looking assessment of the resilience of the domestic retail banking system. (This is a watershed moment for us, the first time that such a modelling exercise has been put into the public domain since the last crisis.)

Why are we so interested in this particular topic? And why now? Well, the retail banks are at the heart of the domestic macro-financial system, providing a number of previously discussed essential services without which our economy simply could not function. Central to our own financial stability mandate is the resilience of the banking system: we want the system to absorb, rather than amplify, adverse economic events, with banks continuing to serve the needs of households and businesses in times of stress. Banks were at the epicentre of the last crisis, curtailing lending supply in response to self-created funding and solvency difficulties, and, as a result, amplifying the shock. A key objective of all our actions is to avoid a repeat of this type of "feedback loop".

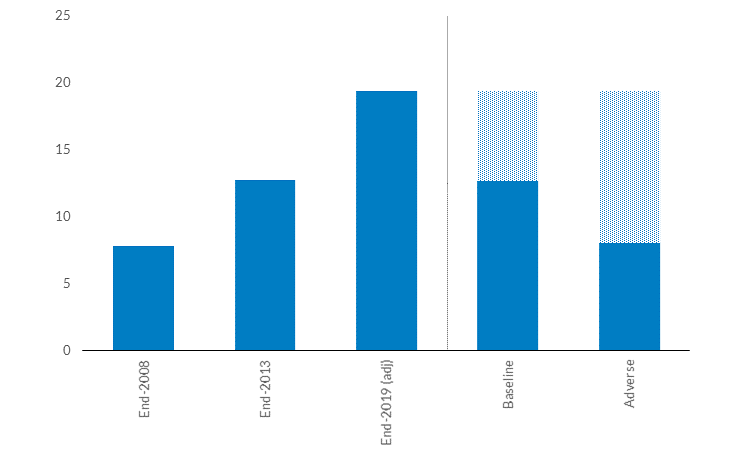

So far the response to the pandemic has had a modest impact on banks’ reported key capital ratios, while borrower default and insolvency rates also remain stable (largely as a result of policy support, payment breaks and the natural lag between economic shocks and borrower defaults). But banks remain exposed to the ongoing economic effects of the pandemic, notwithstanding their stronger loss-absorbing capacity than back in 2008 (see Figure 3). Our forward-looking assessment of the resilience of the domestic retail banking sector looks at capital ratios under two macroeconomic scenarios from 2020 to 2022, one our baseline and the other a more adverse scenario (which assumes a repeat of the economic effects of this year’s public health restrictions, and a more sluggish global economic recovery).

While the immediate economic shock related to the pandemic is roughly comparable with the 2008/09 experience, both the nature of the shock and the starting positions are significantly different. In particular, we don’t have a credit-fuelled real estate boom and other large macro-economic imbalances, nor unstable bank funding conditions.

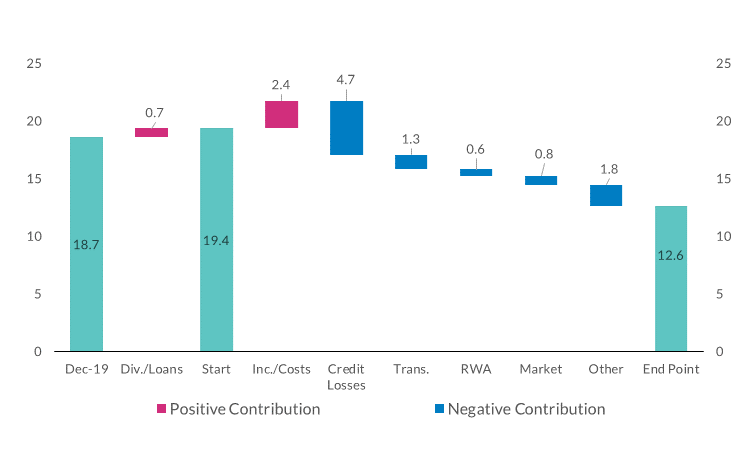

Overall, our forward-looking assessment finds that the retail banking system is in aggregate capable of absorbing shocks that are materially worse than current baseline projections. (Figure 3 shows the projected falls in capital ratios under our baseline and adverse scenario, and also gives some historical context on capital levels in Ireland over the past decade or so. Figure 4 gives a bit more detail on what drives the fall in capital (for our baseline scenario) with credit losses being the key element.)

But, as I said at the start of this blog, the outlook is characterised by huge uncertainty, and the aggregate picture inevitably doesn’t reflect the effect on individual banks (which will depend on their risk profile and financial resources) and underscores the need for ongoing vigilance by management and the Central Bank.

Figure 3: Resilience assessment results with aggregate capital position since financial crisis

Source: Central Bank of Ireland.

Notes: System-wide CET1 capital ratios reported. Shaded areas are capital depletion levels in the Central Bank’s 2020 resilience assessment.

Figure 4: Baseline Scenario CET1 Capital Waterfall

Source: Central Bank of Ireland

Notes: Purple bars imply a positive contribution to the capital ratio, while blue bars imply a negative contribution. Opening CET1 ratio reported on a transitional basis, with all expected unwinding of transitional effects over the scenario horizon subtracted from CET1 over time. Five retail banks included in resilience assessment. The starting point includes the impact of the dividend reversal and loan sales (“Div./Loans”). “Inc./Costs” refers to income and costs, “Trans.” refers to transitional arrangements, “RWA” refers to risk weighted assets, “Market.” refers to market risk losses and “Other” refers to conduct risk, operational risk, known future regulatory developments and other factors affecting the capital ratio.

Policy decisions

Let me conclude with three policy decisions we announced yesterday.

First, our annual review of the mortgage measures where we concluded, after extensive analysis and stakeholder engagement, that they continue to meet their objectives and should remain unchanged for 2021. The measures are aimed at strengthening borrower and lender resilience (as well as reducing the likelihood of an adverse credit-house price spiral emerging) and it is clear they have put borrowers in a better position going into the COVID-19 shock than the financial crisis: our analysis of the initial payment break data shows that borrowers with mortgages issued at lower loan-to-income values were less likely to be in financial distress.

Second, we also announced that the Countercyclical Capital Buffer (CCyB) should be retained at zero per cent, with no change expected in 2021. We made it clear when we released this buffer in March that we expected banks to use its positive effects solely in support of the economy and not for dividend distributions. Given the uncertainty surrounding the outlook and our assessment, as well as the need for the State and the financial system to start preparing to rebuild their buffers, we will need to think very carefully about any suggestions that banks (and insurance companies) should return to paying dividends as they did before March any time soon.

Finally, we confirmed that we will continue to develop our macroprudential framework further in three areas, (1) bank capital (to deepen our understanding on the interaction between the macroprudential buffers themselves and with other policies during periods of growth and periods of stress), (2) the mortgage measures (looking at the overarching framework as well as expanding our public engagement on the operation of the measures) and (3) market-based finance (where, as I’ve mentioned before, we will work with our European and international partners on the development of a comprehensive macroprudential framework in this area).

Conclusion

The twice-yearly Financial Stability Reviews are important milestones for the Central Bank, reflecting a core part of our mandate. This year’s two reviews (the first was published in June) have been undertaken in conditions of remarkable uncertainty but with the same focus that underpins everything that we do: to ensure the financial system works for the whole community, both in good and bad times. I am very proud of the Central Bank’s people for their valuable contributions to this latest FSR.

Gabriel Makhlouf

Read More