COVID-19 and the Financial System

23 April 2020

Blog

Last week I wrote about how COVID-19 is affecting the global and Irish economies. Today's post is about the role of the financial system in the economy as it copes with the impact of COVID-19 and what we at the Central Bank of Ireland are doing about it.

The "financial system" is at the heart of every modern economy. It has many "actors", including financial service providers like banks, credit unions, insurance companies, funds, and asset managers among others. Consumers of financial services include individuals, households, businesses and governments, while central banks and regulators are crucial parts of the architecture of the financial system. The system enables the transmission of resources through an economy, intermediating between individuals, households and firms who represent an economy's borrowers and savers. Savings are channelled towards investment, towards people purchasing a property or starting a business for example. Risks can be shared through insurance, which can be obtained for protection against the uncontrollable events which may affect us. And, of course, payments can be made for goods and services in a safe and efficient manner. When the system works well, resources are allocated efficiently and satisfy the needs of the community that, at the end of the day, represents "the economy".

So the financial system matters. In 2007–09, the system failed and the last decade has seen a focus—across the world—on strengthening its resilience. The economic crisis we are in now has not been caused by the financial system. It is a result of the—very necessary—response to ensure our health services are not overwhelmed (and, ultimately, solving the health crisis is a pre-condition to solving the economic one). Capital and liquidity buffers have been built up since the last crisis, in Ireland and around the world, which leaves the system much better placed to withstand shocks1. And the immediate response to the crisis has shown that the build-up of the system's resilience has paid-off.

We want the financial system to absorb—and not amplify—the economic shock, and to support the recovery. That's been the focus of the Central Bank and our partners in Europe. Our actions can be seen in two overlapping and inter-related phases:

- Ensuring that the financial system is better placed to support households and businesses through the crisis

- Supporting the recovery out of the crisis.

Ensuring the Financial System Can Support Households and Businesses Through the Crisis

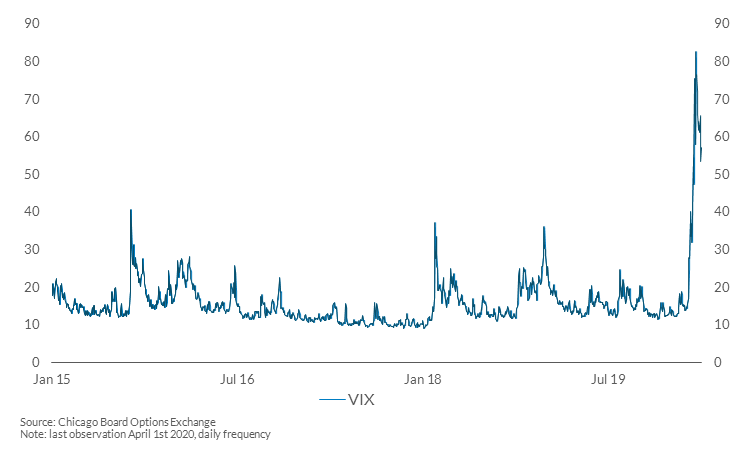

Choosing to put an economy "on hold" is an unprecedented event and the immediate market reaction reflected the repricing of assets amid enormous uncertainty that existed across the world from the pandemic.

Figure 1: Vix Index

At the ECB, my Governing Council colleagues and I agreed on a package of monetary policy measures designed to safeguard liquidity conditions, protect the flow of credit to the real economy, and prevent a pro-cyclical tightening of financial conditions. We decided to make additional asset purchases (amounting to 7.3 per cent of euro area GDP or €1 trillion) between now and the end of the year. We also eased the conditions on our targeted long-term refinancing operations (TLTROs), which stimulate credit supply and incentivise lending to the private sector. The main Irish retail banks could potentially borrow around €20 billion through just one of these operations2.

The ECB's Supervisory Board also provided capital relief for banks amounting to €120 billion, which could be used to absorb losses or potentially finance new lending. This capital relief means that banks can absorb greater potential losses without needing to take short-term action such as selling assets to meet regulatory ratios. This type of behaviour could pro-cyclically amplify the downturn.

At the Central Bank, we followed this up by reducing the counter cyclical capital buffer (CCyB) from 1 per cent to zero per cent3. The CCyB is one of the measures introduced in 2015 to strengthen banks' resilience and ensure they hold sufficient capital to maintain the flow of credit to the economy during periods of financial stress. Releasing the buffer (by reducing it to zero) helps the banking system to both absorb COVID-19 related losses and support the economy. (The capacity for new lending could range from €10–16 billion if used entirely for that purpose.)

These early actions helped to reduce the uncertainty and volatility in markets, reducing in turn the potential for the financial system to amplify the shock and also putting in place conditions to support the recovery.

In particular, the actions helped to support the Government's own response to the crisis. As we have seen, the sudden and large shock to household finances has required extraordinary policy intervention, by fiscal and monetary authorities. In their absence, the downturn will be more severe and the recovery more restricted. From an economic perspective, the condition of household balance sheets will be a key factor in the macroeconomic recovery from the crisis.

The Central Bank is also working with financial service providers to ensure that households and firms are protected throughout this period. This is an active and ongoing engagement. For example, payment breaks on mortgages, and other similar temporary relief measures, allow households and businesses to absorb the shock of the crisis, so that as many as possible can recover once the virus is under control. They will help households and businesses to preserve their liquid reserves today, to the extent possible, at the cost of higher repayments (or longer repayment periods) in the future. These measures do not come without cost.

Supporting the Recovery out of the Crisis

Our immediate focus has been on actions that the financial system as a whole can take to support households and firms through the crisis. Within the Central Bank, we have established a COVID-19 Crisis Response Task Force, with a series of work streams covering subjects such as financial and operational resilience, funds and bank liquidity, forbearance and consumer-related issues. (The Task Force builds on the work of our incident management team that had been operating from 20 February and which enabled us to move to working remotely by the middle of March.)

We are also turning our minds to what will be required to support the recovery itself. In particular, a strong and resilient financial system will be required to support a recovery from what could be one of the deepest—if not the deepest—recessions in Ireland's history. Ensuring that balance—a supportive financial system through the crisis that is ready to finance the recovery from the crisis—is a particular focus for us at the Central Bank and for regulators across the world.

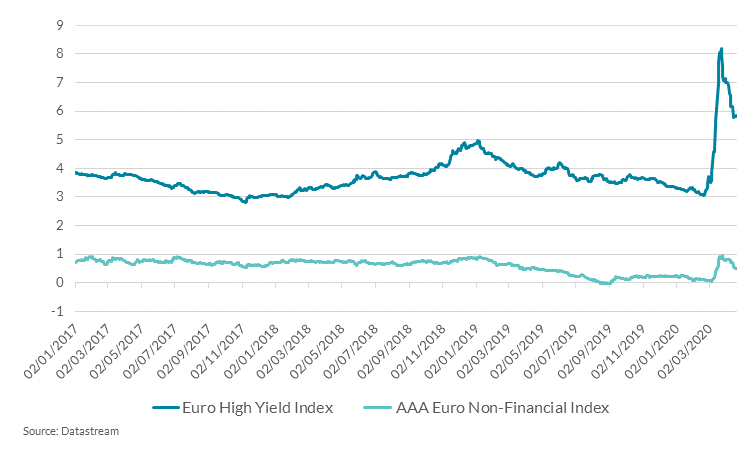

The list of issues we are thinking about is therefore extensive. For example, a few weeks ago we were very focused on developments in global markets, including a deterioration in market liquidity conditions, an acute flight to safety by investors internationally and outflows observed from some types of funds globally. Those pressures have abated due to action taken by central banks. But the measures we have taken are no reason for complacency. COVID-19 is an exceptional shock and we may have a bumpy road to travel yet4.

We have seen large falls in some asset prices and a tightening of financing conditions around the world. This has negative implications for macro-financial conditions across the euro area and at home, especially in key asset markets that are sensitive to the significant macroeconomic shock of COVID-19. Despite the considerable measures taken, depending on the depth and persistence of the shock, we may see further strains in sovereign debt markets because of the economic and fiscal costs of dealing with the crisis, and in financial intermediaries if we see further financial stability risks materialise.

Figure 2: Euro Area High-Yield and Investment Grade Corporate Bonds Index

Apart from looking at the resilience of the financial system as a whole, we are also thinking about the resilience of businesses in view of the important role they play in society.

For example, SMEs account for over 1 million employees, or nearly 70% of total employment in the Irish business economy and they will form an important part of the economic recovery when it comes5. The crisis means many of them are sustaining losses, which threaten their survival; one of the main objectives of policymakers is to ensure that viable businesses are able to weather the storm and so help the economy to recover. A resilient financial system is key to enable firms to access liquidity. The banking system would be expected to play a role in providing that liquidity and the actions we have taken mean that banks are better placed to meet demand for credit from firms (whether that is through drawing on existing credit lines or the extension of new credit). But—as our research has shown—there are also a number of frictions which mean the banking system on its own may be an insufficient source of liquidity. For example, some firms may not have an existing relationship with a lender or may have insufficient collateral to secure a loan. In addition, the willingness of lenders to lend may adjust as the economic shock evolves or as they respond to actions by third parties, whether competitors, governments or regulators. (We will soon publish some research on the potential liquidity needs of SMEs.)

Conclusion

All of our actions have been aimed at ensuring the financial system absorbs the shock, is better placed to support households and businesses through the crisis, and can support the recovery. All the measures are designed to support consumers and businesses. They ensure supportive financing conditions and enable banks to absorb losses and support lending to businesses and households. They support households in rebuilding their balance sheets and support governments by ensuring that interest rates on sovereign debt remain low.

We have been able to take these actions because of some of the important policies that were introduced over the last decade, policies that have increased the resilience of banks, households and firms so they can better withstand shocks. The focus of all these policies—from bank capital buffers and the mortgage measures through to regulations for lending to SMEs—is the protection of all consumers across the country. They will prove to be critically important over the coming period.

Of course, we couldn't have predicted a pandemic like COVID-19, but a small open economy like Ireland is always more vulnerable to shocks in a globally interconnected economy. I spoke about this, and economic resilience more broadly, in Waterford back in November last year6 and will probably return to the subject in a future post.

Gabriel Makhlouf

1 Sharon Donnery (2018). 10 years on—what have we learned.

2 Sarah Holton, Gillian Phelan and Rebecca Stuart (2020). COVID-19 Monetary policy and the Irish economy. Vol.2020, No.2 (PDF 738.45KB), Economic Letter Vol.2020 No.2.

3 Denora, O'Brien and O'Brien (2020). Releasing the CCyB to support the economy in a time of stress (PDF 641.11KB), Financial Stability Note No.1.

4 See the recently released Stability Programme Update from the Department of Finance.

5 CSO (2017). Business in Ireland 2017.

6 Gabriel Makhlouf (2020). Resilience through transitions: facing the tumult - Governor Gabriel

Makhlouf.

Read more