Non-Performing Loans: The Irish perspective on a European problem - Deputy Governor Ed Sibley

22 September 2017

Speech

Introduction

Good morning. It is a pleasure to be invited to speak at the second annual ESRB conference.[i]

As the Chair and previous panellists have noted, non-performing loans (NPLs) have many dimensions. They affect the credit supply channel, impact on banks’ financing costs, bring uncertainty to banks’ capital position, and block-up capital that could otherwise be used for more economically and socially useful activities. They also cause considerable distress for borrowers.

In short, they can cause serious dysfunction for the banking system and hence its ability to serve the economy and its customers.

For me, as a member of the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) Supervisory Board, NPLs clearly remain one of the central challenges facing the European banking sector today.

NPLs go to the heart of banking - both its simplicity and its complexity. Because credit, like banking more generally, ultimately requires trust. High levels of NPLs can erode that trust and confidence in the banking system.

In my remarks today, I would first like to reflect on this issue of trust. I will then elaborate on the Irish experience, pointing to some of the measures and solutions we took regarding NPLs. Finally, I would like to draw on some of the key lessons from the Irish experience, which are relevant to the broader trajectory for Europe going forward.

Trust and NPLs

Both maturity transformation and credit intermediation ultimately rely on trust.

At its simplest, depositors need to trust that when they put their money into a bank they have certainty of being able to withdraw that money in the future. Similarly, banks need to trust that when they gather these deposits, and lend at longer maturities, they will either be repaid, or in extremis be able to enforce collateral. This requires trust in the legal, judicial or extra-judicial processes.

However, we have all seen how trust can evaporate very quickly in times of crises. And, as Francis Fukuyama notes, “widespread distrust in a society….. imposes a kind of tax on all forms of economic activity”.[ii]

While trust and confidence may be considered intangibles, the quantitative impacts are demonstrated through hard numbers. For example, investor mistrust will be reflected in lower price to book ratios; banks’ mistrust will be reflected in elevated interest rates to compensate for higher risk; potential new entrants and consolidators mistrust will be reflected in the reduced likelihood of entering markets with higher NPLs, and so on.

Authorities, including supervisors, therefore have a critical role in ensuring trust within the system.

The SSM is close to three years in operation. It is still a relatively new institution. Much has been done to establish its reputation as an effective, intrusive, and independent supervisor.

This trust is hard-earned and easily lost. By taking the necessary decisions, by doing the right things we will continue to earn the trust of the European public and market participants. And this includes taking firm action in relation to NPLs.

But it is not easy. We must consider financial stability issues, and perhaps less obviously for some prudential supervisors – but crucially nonetheless – consumer protection matters. Prudential supervision and consumer protection are inherently interlinked and mutually self-reinforcing. Poor outcomes for consumers are poor outcomes for the banking system.

Although the ECB does not have an explicit mandate for consumer protection, many National Competent Authorities – such as the Central Bank of Ireland – do. Even were that not the case, it is important that intrusive prudential supervision should not come at the cost of the consumer.

And this is particularly relevant for action on NPLs, which by its very nature relate to dealing with distressed borrowers – that may, for example, be at risk of losing their family home, or small enterprises that are providing local employment.

Indeed, ensuring that borrowers are protected remains at the heart of the Central Bank of Ireland’s approach to NPLs. This is a fundamental aim in its own right, but it is also important in rebuilding trust in the Irish financial system more broadly following the crisis.[iii]

I am cognisant that there is much more to be done in this regard, and the remaining high level of NPLs is a significant drag on rebuilding this trust across the system.

The Irish experience with NPLs

This brings me to our own experience in Ireland.

The Irish banking sector has been transformed since the start of the crisis. Intensive supervisory focus and pressure coupled with improved economic circumstances continue to drive reductions in NPLs.

Nevertheless, NPLs levels remain elevated and their sustainable resolution remains a key supervisory priority.

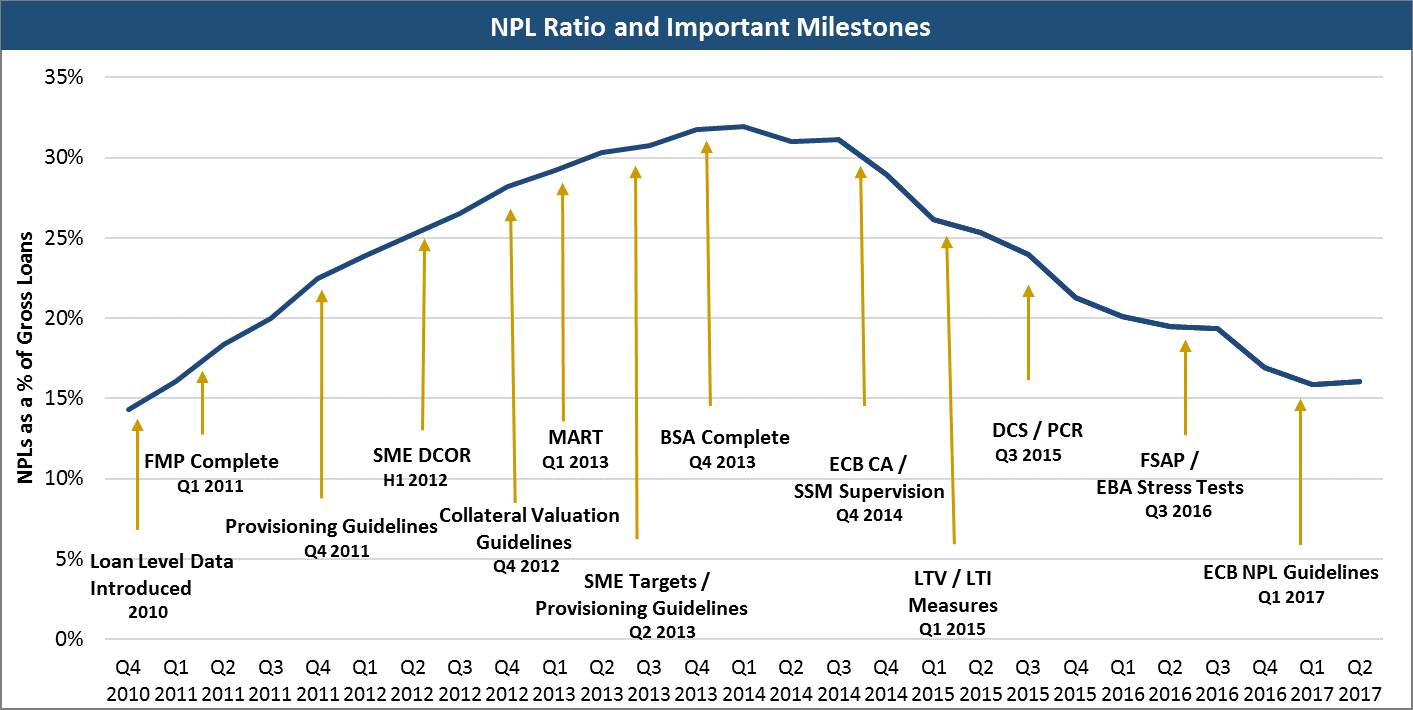

This chart helps to illustrate this story, and the increasingly intrusive actions that have been taken to drive NPL reduction:

Source: Central Bank of Ireland regulatory returns. At Q3 2014 the EBA’s harmonised definition of non-performing was introduced. Prior to this date, an internal definition was used equivalent to impaired loans and/or arrears > 90 days.

Prior to the crash Irish bank balance sheets expanded considerably, with domestic Irish banks more than tripling their size.[iv] This increase was heavily driven by property related exposures facilitated by weak lending standards and practices (e.g. high LTVs) and ultimately unsustainable business models.

The economic downturn and bursting of the property bubble resulted in large bank losses (the six largest banks lost approximately €67.8bn between 2008 and 2012).

The National Asset Management Agency (NAMA) was established in December 2009 as one of a number of initiatives taken by the Irish authorities to address the serious problems in the banking sector. The Agency acquired the largest commercial real estate and connected exposures held by the Irish banks, with a nominal value of €74bn. The objective was to deal with the largest and most problematic loans in the banking system and to, subsequently, obtain the best achievable financial return for the State on this portfolio over an expected lifetime of up to ten years.

Interestingly though, as the chart above shows, NPLs - amounting to €85.3bn - only peaked in Ireland in Q4 2013, with an NPL ratio of 31.8%, more than two years after loans were transferred to NAMA. So, although NAMA was clearly a critical part of the solution to dealing with the banking crisis in Ireland – particularly with respect to the larger commercial real estate loans – it was by no means the silver bullet some people may think for resolving Irish NPLs overall, as SME and mortgage loans remained a serious and growing problem.

Of critical importance during 2010 and 2011 was ensuring that the banks were adequately capitalised, impairments were recognised, and adequately provided for. The work involved an assessment of asset quality, and stress testing the banks' balance sheets.

An important milestone was the work conducted by the Central Bank of Ireland during the Financial Measures Programme (FMP). Under the FMP, a balance sheet assessment and stress test exercise was completed in 2011 and resulted in a total capitalisation requirement of €24bn for the going-concern banks.

Following the recapitalisation in 2011, which we must not forget was at a catastrophic cost to the Irish taxpayer, our supervisory focus turned to banks’ NPL resolution strategies and capabilities. They were wholly inadequate.

The Irish banks remained too slow to recognise the problem and in many cases were still reluctant to deal with it. Furthermore, they did not have credible strategies, nor the operational capability to resolve it. Indeed, there are short-term incentives for individual banks and management to try and avoid resolving large scale NPLs, in the hope that economic recovery will deal with the problem. But evidence shows that while this reluctance may be understandable at an individual bank level, the macro impact of not dealing with NPLs is highly problematic for the system as a whole.

The Central Bank of Ireland therefore became more prescriptive and expectations were clearly set out to the banks, including: segment specific strategies, detailed implementation plans, and enhanced board ownership.

Key elements included banks setting out clear plans on how they were going to address NPLs. Portfolio specific NPL strategies, for example, Mortgage Arrears Resolution Strategies (MARS) were required from the main lenders. Banks’ boards were required to approve these strategies encompassing the fair treatment of customers and ensuring adequate capabilities to deal with each customer.

Consumer protection measures such as the Code of Conduct on Mortgage Arrears and enhanced SME protections ran alongside and were interlinked with the prudential measures.

We assessed each lender’s strategy and plans, and reverted with firm-specific feedback, follow up actions and timelines in early 2012. While operational capability had been improved, we remained concerned that banks were overly reliant on short term forbearance or “extend and pretend” strategies. In other words, they were still dragging their feet.

So, to press banks to implement longer term sustainable solutions, we introduced Mortgage Arrears Resolution Targets, underpinned by giving guidance on our view on sustainable solutions that both protected engaging borrowers as well as driving resolution. We also introduced non-public SME Targets for banks.

You will also see that the Central Bank introduced and subsequently updated provisioning guidelines to ensure that there was consistency and conservatism in the recognition and provisioning of NPLs.

Towards the end of the Programme, in 2013, we then repeated the exercise of assessing the strength of the banks’ balance sheets, the adequacy of capital and the recognition of NPLs.

We challenged progress every step of the way, going to the outer edge of our remit to do so – challenging the organisational structure and resource capacity, challenging skills and experience, challenging governance and oversight, policies and procedures, workout strategies and execution ability.

We challenged the implementation of the plans, challenged credit management and impairment recognition, challenged provision coverage and collateral valuations, challenged short-term vs sustainable resolutions.

And we continue to challenge the Irish banks today.

And while it is slower than I would like, this approach is working. This has been achieved through better cohort by cohort borrower engagement strategies, working out and sustainably restructuring loans, and some portfolio sales. Importantly, legislation has been passed to enable borrower protections to travel with loans that have sold outside of the banking system. Accounting write-offs have not yet featured to the extent warranted.

NPLs in Ireland have reduced for fourteen consecutive quarters. It represents a 58% reduction from peak, a decrease of over €50bn. In some ways, this graph understates the progress, because the NPL ratio has been materially reduced at the same time as there has been a very sizeable deleveraging in the system – loan books (both good and bad) in aggregate are much reduced.

But there remains much more to be done, primarily now on long past due mortgage arrears, which remain a blight for distressed borrowers, banks, and the system as a whole.

The reason I am recalling recent Irish history, is that, in many respects the journey we took in Ireland is now being followed at a European level.

Asset quality and balance sheet strength has always been a priority for the SSM, as evidenced by the Comprehensive Assessment in 2014. When it took on supervisory responsibility for Europe’s banks, the NPL outlook was diverse across the euro area. While certain countries’ banking sectors had, and still have, low NPL ratios, it was recognised that even those countries where banks were not struggling with asset quality, may be affected by spillovers.[v]

Through the Comprehensive Assessment, the SSM took early action to gain assurance that problem loans were recognised and that the system as a whole had sufficient capital to manage the problem, both under a base and stress scenario, in the same way as it had been done in Ireland in 2010 / 2011.

Yet NPLs have remained stubbornly high. The banks’ responses to the NPL problem have disappointed, in the same way as the Irish banks’ initial responses did.

Issues regarding recognition and provisioning for NPLs persisted. Strategies and capability for dealing with them were inadequate. Individually, banks did not appear sufficiently incentivised to address the problem. Furthermore, structural issues in different jurisdictions were causing significant issues.

Following the establishment of an SSM NPL Taskforce, and much work on data collection and jurisdictional differences and approaches, in March this year, the ECB published the final Guidance to banks on non-performing loans. The Guidance sets the SSM’s expectations on NPL management – and prescribes that banks should implement ambitious yet realistic strategies to reduce their NPLs, using a very granular, portfolio-by-portfolio approach. They must also set internal targets to reduce their NPLs. This does not necessarily mean portfolio sales. The hard yards of engagement with distressed borrowers, workout, restructuring and right-sizing debt must also be cornerstones of successful NPL reduction. Banks should also be taking action through their accounts to reflect the reality of the collectability of long dated NPLs.

Those strategies are currently under the scrutiny of the Joint Supervisory Teams (JSTs), and have become the basis of the day-to-day supervisory dialogue with banks.

It is still early in the process for the implementation of the Guidance, and many banks have submitted credible plans. However, many more still need to improve – indeed some were wholly inadequate and in those cases, banks have been required to resubmit.

The Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP) continues to underpin the SSM’s approach to NPL resolution – imposing quantitative capital and qualitative remediation requirements as part of our annual risk assessment of each significant bank.

Lessons from the Irish crisis

I would like to highlight three key lessons from the Irish experience that are relevant from a European perspective.

Firstly, left to their own devices, individual banks will not resolve Europe’s NPL problem, no matter that it is primarily their responsibility to do so.

Intensive, courageous and outcomes-focused supervision is required. And it is not just a one-off effort – it needs to be continuous and persistent, driven by high quality analysis. When we get to the end of the cycle of work we need to start again at the beginning.

The ECB Guidance to banks on non-performing loans is therefore a very important step towards NPL resolution across the European banking system.

Secondly, it is clear from the Irish experience is that no single measure will resolve NPLs.

Supervisors cannot solve it all alone. What has helped Ireland is the combination of factors: including NAMA, increasingly intrusive and prescriptive supervisory measures, and some legal initiatives. The interplay with economic recovery is obviously hugely important also.

As highlighted by the July 2017 ECB stocktake report on national supervisory practice and legal frameworks related to NPLs, a number of structural obstacles still prevent banks from resolving their NPLs in a timely fashion across the euro area. These include lengthy legal procedures, tax and indeed accounting impediments. Action on all fronts is therefore required – even if Member States do not have high levels of NPLs.

Thirdly, the consequences of a credit boom gone bust are very severe, and can take a huge amount of time to address. Whilst we have made significant progress in addressing NPLs in the Irish banking system, NPL workout and resolution takes time, even with a buoyant economy. Early intervention is therefore critical in to achieve the best outcome for both borrowers and banks.

Moreover, intrusive supervision of current underwriting practices as well as continually assessing the long term sustainability of business models are crucial to prevent recurrence, even as we are still dealing with the legacies of the past mistakes.

Conclusion

Much work remains for the Irish banks to do, and for European banks as a whole. First and foremost, banks must act themselves. But where they do not, or are too slow, or not ambitious enough, it is our job as supervisors to drive them to do so.

In the Central Bank of Ireland, we continue to work tirelessly to earn the trust of the Irish people, both in the work we do ourselves and in the financial system as a whole – such that it is demonstrably serving the long term economic needs of the country and its customers in a sustainable way.

The Central Bank of Ireland will continue to play an active and supportive role in the SSM, as it continues to build its reputation and trust with the public and with the market, not least with respect to our contribution to the ECB’s work on NPLs.

Thank you for your attention, I look forward to the discussion.

[i] I would like to thank Mícheál O’Keeffe, John Cullen and David Duignan for their contribution to my remarks.

[ii] Fukuyama, Francis. 1995. Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity. New York: Free Press.

[iv] From January 2003 to December 2008, domestic banks balance sheets grew from €233bn to €806bn, respectively. This represented an increase of 345%;