Non-banks: Learning from experience

09 November 2022

Blog

As I wrote in my last blog, one of the messages from my attendance at the IMF’s Annual Meetings last month is the significant uncertainty that policy makers face. Russia’s war against Ukraine and the resulting energy crisis have added considerable

downside risks to the global economy and financial system. Persistently high levels of inflation have become even more broad-based, requiring a larger and more rapid monetary policy response than was previously expected. As a result, global financial

conditions are tightening, with necessarily higher interest rates leading to asset price adjustments in many markets, limiting fiscal space, slowing economic demand, and pressuring borrowers’ debt-servicing capacity across the globe.

We will be reflecting on what these developments mean for the financial system as a whole in our forthcoming Financial Stability Review. But, I wanted to focus this blog on one issue which I mentioned in my remarks last week at our first Financial System

Conference; Non-Banks. Globally, the non-bank sector has grown rapidly over the past decade. In fact, data from the latest FSB Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation shows that non-banks grew by approximately 94% between

2010 and 2020. Ireland has a very large, international-facing non-bank financial sector. The funds sector is the largest part of Ireland’s non-bank financial sector, with Investment and Money Market Funds holding approximately €4.2tn assets

under management (AuM) at end-June 2022.1

Market-based finance provides a valuable alternative to bank financing and can facilitate risk sharing across the financial system. In doing so, it can support economic activity. Like all forms of financial intermediation, however, market-based

finance can contribute to a build-up of financial vulnerabilities. If you look at previous episodes of financial stress, two key sources of vulnerabilities appear time and again: excessive leverage and excessive liquidity transformation. And, when

shocks hit, they can transmit through interconnectedness between different segments of the financial system.

We saw how liquidity mismatches in open-ended investment funds can exacerbate shocks to market functioning during the COVID-19 shock.2 The recent stress in the UK gilt market illustrates how leverage-related vulnerabilities in the non-bank

financial sector can be exposed by deteriorating market conditions, and how such vulnerabilities can amplify shocks to financial markets.

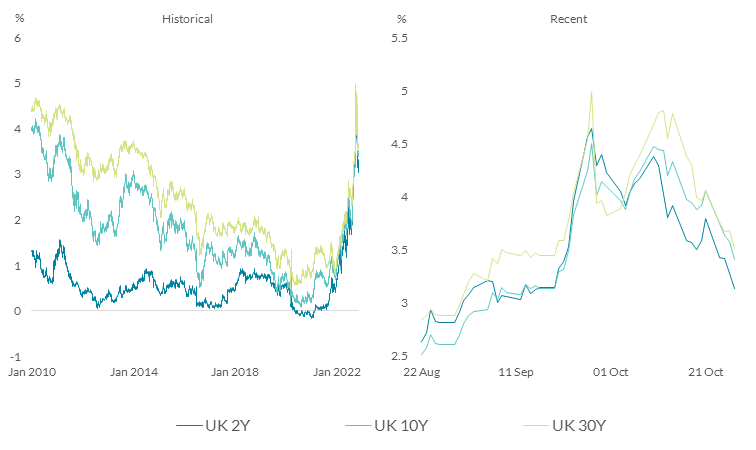

The UK Government’s announcement on 23 September led to a strong and negative market reaction. 30-year gilt prices fell by more than 24 per cent between 22 September and early morning 28 September (See Chart 1). The dislocations in the UK gilt markets

were triggered by market participants’ perceptions of the macro-economic and fiscal implications of the UK’s mini-budget. This, however, was not just a case of re-assessment of underlying risk. Market dislocations were amplified by liquidity

strains amongst Liability-Driven Investment (LDI) strategies employed by pension funds, many of which relied on high level of leverage to make returns. The drop in the value of gilts meant that the pension funds’ investments in the LDI strategies

were at risk of being wiped out, or turning negative in value. Furthermore, the LDI funds experienced significant margin and collateral calls following the rise in yields, requiring them to sell gilts amid poor liquidity conditions, further adding

to market pressures.

The effects of the stress in gilt markets were not limited to the financial sector. There were also implications for the real economy, with reports of sharply rising yields feeding through into increasing mortgage rates.3 The Bank of

England (BoE) intervened in the market on 28 September, announcing it would buy up to £65bn worth of gilts up to 14 October in order to restore stability to the market. This was alongside other targeted measures such as expanded collateral eligibility

and a temporary repo facility. The markets rebounded 24 per cent in a matter of hours but significant volatility remained over the following weeks. Markets have stabilised now, with gilt yields generally returning to the same levels or even below

where they were prior to 23 September, though market uncertainty about the medium-term UK fiscal strategy appears to persist.

Let me explain a little bit more the mechanisms of these LDI strategies and how leverage-related vulnerabilities can add to market pressures in times of stress. LDI funds are used by defined benefit pension schemes to hedge the interest rate and inflation

sensitivity of their liabilities. The LDI funds employed significant amounts of leverage, with many essentially borrowing to gain additional exposure to gilt markets. This allows the pension schemes to maintain their liability hedge without committing

all of their assets to the LDI strategy, but also increases their sensitivity to market movements. A significant number of UK pension funds employed LDI funds that are domiciled in Ireland, though LDI funds and investment strategies are pursued in

other countries as well.

LDI funds primarily manage their leverage using the concept of headroom, a buffer to allow them to absorb market fluctuations. However, the movements in the gilt markets on 23 September and subsequent days were far higher than seen in recent history,

beyond the severe but plausible scenarios typically applied in portfolio stress testing. This caused the headroom to be either significantly depleted or wiped out. The LDI funds were forced to sell gilt assets, amplifying the already falling gilt

markets. The BoE’s intervention restored market functioning and gave UK pension funds and the LDI fund managers time to increase their headroom (i.e. reducing their leverage) by either increasing pension funds’ equity contributions into

LDI funds or by reducing their market exposure.

Irish-domiciled funds have large international exposures. This means that, when global shocks hit, these can transmit to the funds sector resident here. This was the case with the market turmoil in the gilts market. Irish-resident LDIs funds, in particular,

have significant exposure to the UK gilt market. Investment funds authorised by the Central Bank have aggregate holdings in UK gilts of approximately £267bn, representing approximately 6% of total AuM. Of that £267bn, LDI funds represent

the largest sub-component of UK gilt holdings by Irish domiciled funds. In response to the market turmoil, we engaged closely with both market participants and UK and other international authorities. A more damaging crisis was averted by a combination

of the Bank of England’s market intervention, actions taken by market participants to reduce leverage on the back of supervisory engagements and effective cross border regulation. These collective actions introduced increased resilience in the

LDI sector to future market shocks. Given the adverse medium term outlook for macro financial conditions we expect that this increased resilience is maintained.

The events highlight the fragility of certain segments of the global financial system, given the prevailing risks related to tightening financial conditions and deteriorating market liquidity, amid elevated global indebtedness. They also highlight how

the evolution of the financial system, especially the non-bank sector, can become a source of vulnerability, with adverse effects on market functioning.

These factors further underline the need for well-developed macroprudential policy for non-banks, including investment funds, to ensure market participants are resilient to market shocks, thereby avoiding damaging amplification mechanisms. I see this

as a strategic priority for both the Central Bank of Ireland but also for the wider international regulatory community. One example of that is the macroprudential measures that we have been consulting on to limit leverage and liquidity mismatch around

property funds. Irish domiciled funds hold €22.1bn of Irish property and land or approximately 35% of the investable commercial real estate market. This is the most direct link of the Irish-resident sector with the domestic economy. More broadly,

we are working to develop and operationalise a framework for macroprudential policy in the non-bank sector with our European and international partners. Given the global nature of capital markets, this work needs to happen internationally to be effective.

Conclusion

The non-bank sector has grown significantly in the last decade. The recent events in the UK and what we saw two years ago at the beginning of the pandemic were ‘near misses’. We need to move urgently towards developing a framework that tackles

the systemic risks that non-banks now pose to the stability of the financial system as a whole. It is important that we learn the lessons of recent crises and that we shut the stable door in good time.

Chart 1: UK gilt yields - The gilt market moves in the days prior to 28 September were unprecedented, with two daily increases in 30 year gilt yields >35bps, topping the biggest daily increase previously going back to 2000.

Source: Bloomberg and Central Bank of Ireland calculations

Note: Data shows UK gilts for 2 year, 5 year, and 30 year bond yields. Data frequency is daily. Last observation 27 October 2022.

Gabriel Makhlouf

1Non-Bank Financial Sector Statistics

2 FSB (2020) - Holistic Review of the March Market Turmoil

3 Financial Times-Soaring bond yields set to lift UK mortgage rates

Read more: