Inflation dynamics in a pandemic: maintaining vigilance and optionality - remarks by Gabriel Makhlouf

23 November 2021

Speech

Inflation dynamics in a pandemic: maintaining vigilance and optionality - remarks by Gabriel Makhlouf, Governor of the Central Bank of Ireland1

After more than a decade of very low inflation in the euro area, and especially in Ireland, prices for many goods and service's have risen faster in 2021. We know that many people are feeling these very real price increases, in particular across their energy and fuel bills. The key challenge for policy makers now is to assess the extent to which relative prices are adjusting to the ebb and flow of supply and demand in the pandemic environment or whether the fundamental dynamics of the inflation process have altered, resulting in broad-based inflation trends. In these remarks, I outline the main drivers of recent inflation2, 3, the prospects for inflation over our forecast horizon, and what this means for policy.

My starting point is something that I wrote about at the start of the pandemic, paraphrasing the famous opening line from Anna Karenina: “all financial crises are alike but an economic crisis is unique in its own fashion”4. It remains my view that the economic crisis caused by the pandemic – when economies closed down in the way so much of the world chose to – has no precedent in known history. We experienced – and are experiencing – an unusual combination of demand and supply shocks.

Over the last decade, inflation – that is whether consumer prices are rising or falling and by how much – had been very low in the euro area. Ireland was no exception to this general trend with prices for goods and service's rising slowly. As the Irish and wider euro area economy reopened earlier this year, inflation dynamics have been quite different with prices increasing more rapidly.

A key challenge for central banks in the euro area and around the world is how to respond to this change in inflation dynamics. The key judgement we need to make is whether current developments are mainly transitory and will fade over time, or if there have been structural changes that lead to broad-based and persistent inflation trends. In other words, are we going back to familiar territory or to something different?

Today I want to outline some of my thoughts on this key challenge and the judgements that we need to make.

What is driving inflation?

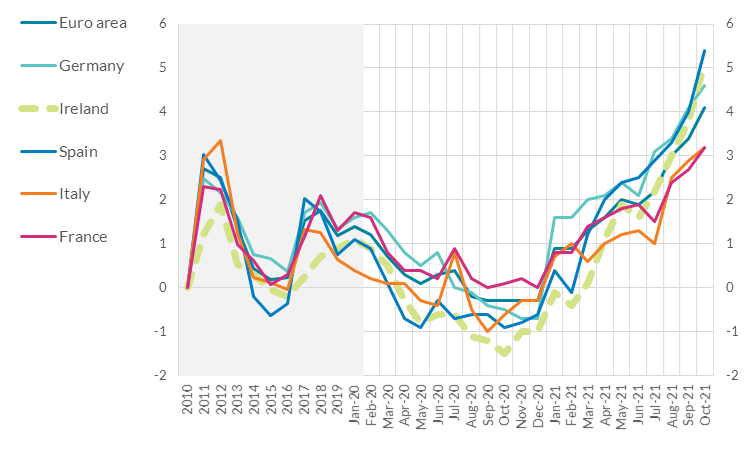

Last year, inflation was very subdued across the euro area, even turning negative for several months as economies closed down to slow the spread of the virus. Coinciding with the easing of health restrictions and increased economic activity, inflation turned positive again in 2021 (Chart 1).

Overall, increasing inflation is being driven by three factors: higher energy prices, a rebound in prices for some goods and service's that fell sharply during the pandemic, and a rebound in demand which is meeting global supply bottlenecks in both inputs and transportation.

Chart 1. Headline inflation, selected countries

Source: Eurostat, data to October 2021.

At first inflation developments in Ireland lagged those of the euro area, in part due to a slower phased re-opening of the economy, but in general they have followed global trends over the last couple of years.

As I mentioned, increases in global energy prices have been a major driver of inflation in recent months, with inflation reaching 5.1 per cent in Ireland in October and 4.1 per cent in the euro area on a year-on-year basis (Chart 2). Energy prices have both a direct and indirect effect on prices people have to pay for goods and service's. The direct effects on home heating or electricity and personal transport fuels – driven in particular by changes in energy prices in international energy markets – tend to pass through quickly to consumers. Indirect effects occur via the impact on business costs and tend to be passed on more slowly and only partly to consumers.

Chart 2. Non-energy inflation (Ireland)

.png?sfvrsn=982c921d_2)

Source: Eurostat, data to October 2021.

The rise in energy price inflation during the first half of 2021 follows on from the fall in prices in 2020 at the onset of the pandemic (so-called ‘base effects’). Given that the prices of some goods and service's fell during 2020 as governments imposed lockdowns, comparing prices from now – when economies have reopened – to last year, can produce a sharp increase in measured inflation even if prices are recovering to pre-pandemic levels. These ‘base effects’ were larger for Ireland, compared with some other euro area countries, simply because prices fell by more in 2020 in Ireland (Chart 1). However, base effects are playing a smaller role in explaining rising energy inflation in recent months: as Chart 3 shows, energy price levels now exceed those before the pandemic. While highly volatile, and often influenced by geo-political factors, market expectations are for wholesale energy prices to plateau in 2022, before declining gradually (Chart 4).

Chart 3. Energy price levels (all components of HICP-Energy)

.png?sfvrsn=a22c921d_2)

Source: Eurostat, data to October 2021.

Chart 4. Energy futures (oil & gas)

.png?sfvrsn=a52c921d_2)

Source: Bloomberg

As well as energy prices, there are three other components of the Irish inflation index that are important to consider: food, non-energy industrial goods (‘goods’) and service's. Increases in food and goods inflation reflect the global factors I have already mentioned, namely global supply and transport bottlenecks. Pass-through from higher energy and input costs is also a factor, and will likely continue to be so for several months yet.

However, the price of service's in Ireland has been increasing through the second half of 2021. Within the service's category, price increases in rents (+6.8%) and restaurants and hotels (+4.2%) stand out. This is not only for the scale of the increases, but also because both categories together account for almost half of all service's spending. Base effects are also relevant in these categories. Relative to pre-pandemic, rents and restaurant and hotel prices are both 4.2% higher according to the Central Statistics Office.5

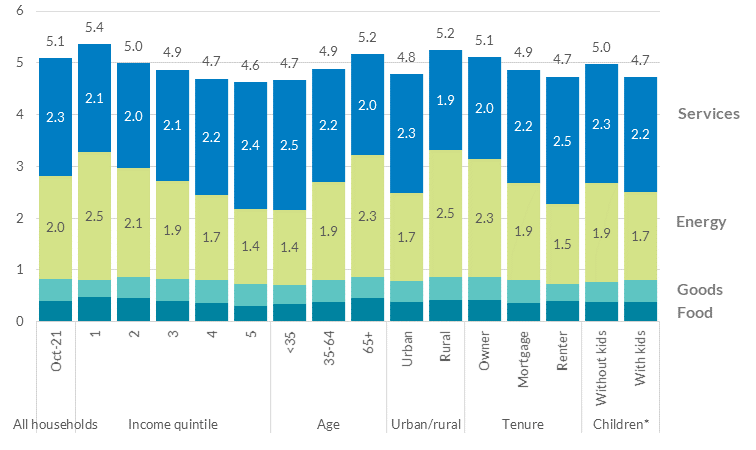

While measures of inflation are designed to represent an ‘average’ consumption basket in an economy, inflation affects people in different ways and not everyone in the community will experience price increases in the same way. Some people will be more (or less) impacted by the recent bout of inflation, simply because they are more or less exposed to certain price changes.

Lower income households, older people, and rural households are more affected by energy-driven inflation. This is because it represents a larger proportion of their spending, compared to other groups (Chart 5). Conversely, higher income households, younger people and more urban households tend to spend more on service's.

So inflation affects different people in different ways.

Chart 5. Share of spending on main inflation aggregates by income quintile

Source: CSO, Household Budget Survey (2015/16). Shares adjusted for change in aggregate HICP weights 2015-2021.

Source: CSO, Household Budget Survey (2015/16). Shares adjusted for change in aggregate HICP weights 2015-2021.

Chart 6. Inflation for different households6

Source: CSO, Household Budget Survey (2015/16)

(*) Working age households with/without children

How should monetary policy respond?

Monetary policy is a relatively blunt tool that aims to affect the economy as a whole and is not an effective policy tool to address distributional issues (unlike targeted measures such as the fuel allowance changes announced in Budget 2022).

As a member of the euro area, Ireland shares a currency and a monetary policy environment with 18 other Member States. Euro area monetary policy is set by the Governing Council of the ECB (of which I am a member) for the euro area as whole and not for any one individual country. Each Member State has its own characteristics – different market structures and history for example – which can mean that there are differences in price developments and in financing conditions across the monetary union.7

The primary objective of the ECB is price stability. Our target is 2 per cent annual inflation in the medium term. Now, why does the ECB aim for small gradual inflation rates? If inflation is too high the purchasing power of money is eroded and it can be challenging for firms to set prices and for people to plan their spending. But if inflation is too low, or negative, then some people may put off spending because they expect prices to fall. If prices are falling continuously across the board (deflation), there is a vicious cycle for the economy. People tend to postpone today’s purchases to take advantage of lower prices tomorrow. In this situation, businesses reduce their wage bills through cutting job numbers rather than wages. Aggregating this up to the economy, we have lower spending, slower growth, less employment and slower wage growth.

By aiming for slightly positive inflation, the central bank ensures a safety margin against deflation, provides space for monetary policy to respond when the economy is hit with shocks, and allows for some mis-measurement of inflation.8

In deciding how to respond to inflation developments, monetary policy makers need to consider two things. First, what is the source of the inflation and how long is it expected to last? And second, what is the potential for more broad-based and persistent inflation above the 2 per cent target in the medium term?

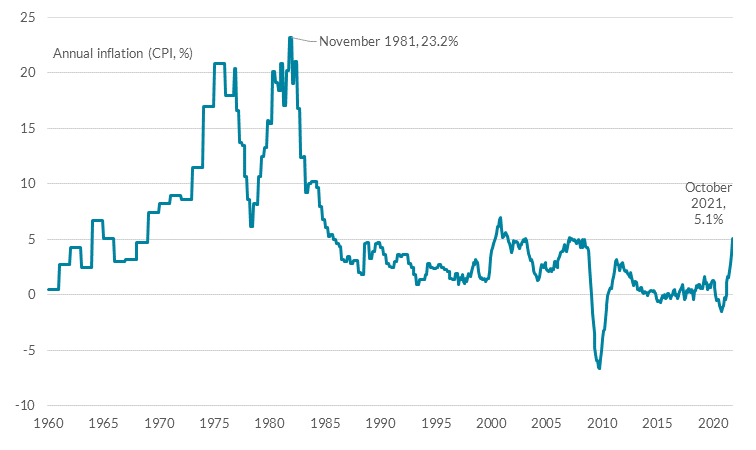

Forecasting future economic developments is always challenging but there is a remarkable level of additional uncertainty and complexity to consider right now. We are not in an ‘ordinary’ economic environment. Our judgement today is that we expect the global drivers of current inflation to recede gradually during 2022. On the potential for relative price changes to lead to more broad-based inflation, monetary policy makers across the world have spoken about so-called ‘second-round effects’ from inflation into wage-setting. This could happen if supply bottlenecks take longer to be cleared than expected, thus affecting inflation expectations, and propelling us into a situation where wages are set in anticipation of inflation in the future being above our 2 per cent target. This harks back to the experiences of wage-price spirals in the past – both in Ireland and many other countries – where increases in the relative price of certain goods and service's raised headline inflation, which fed back into wage inflation as workers sought to preserve real incomes, contributing in-turn to further ‘cost-push’ inflation.

Chart 7. Inflation since 1960

Source: CSO. CPI inflation, annual data from 1960-November Q3 1976, quarterly data to 1997, monthly thereafter.

It is a world we do not want to return to and I do not expect us to do so. That is mainly because the institutional backdrop today is different. We now have an inflation-targeting independent central bank and different wage-bargaining institutions in some countries. In addition, higher inflation rates today should be viewed in the context of a prolonged period of too-low inflation in the euro area. Inflation was clearly below the 2 per cent aim for many years between 2010 and 2021. Inflation dynamics have generally been stronger in the United States than in Ireland and the rest of Europe over that time. U.S. inflation has also been higher in 2021 reflecting, among other things, the contribution of U.S. fiscal policy to demand in the economy. Inflation dynamics are different in the U.S. – as well as in the U.K. – and we should all be cautious about the comparisons we make and the responses we expect from different monetary policy makers operating in different contexts.

Recent data for the euro area (Chart 8) does not suggest, at least thus far, that higher inflation in 2021 is feeding into broad-based higher wage demands, although the upheaval in the labour market makes it more challenging than ever to extract timely and accurate insights from the data.

Chart 8. Negotiated wages and labour cost index (euro area)

.png?sfvrsn=a72c921d_2)

Source: ECB-SDW; labour cost index is a four-quarter moving average. Data to Q2 2021.

Monetary policy’s primary effect is through the demand side of the economy. We therefore need to be conscious of the effects of tightening policy, when the recovery from the pandemic in the euro area remains highly uncertain, and incomplete. The wrong monetary policy action today could prove more costly than the risks stemming from the current spike in inflation. Over the medium term, it could slow economic growth unnecessarily, which could prevent inflation reaching our target in a sustainable manner. And while lower income households suffer more from energy driven inflation, they are also more vulnerable to a contraction in demand that would reduce employment.9 Constraining demand now to bring it back into line with what might be a transitory supply interruption would then depress incentives for supply to return.

Having said that, we cannot afford to be complacent. We need to recognise that there are risks to the inflation outlook. If current trends in inflation persist, the case for monetary policy action becomes stronger. Incoming data do not currently show evidence that would lead us to think that inflation pressures are becoming persistent, but this could evolve and we must remain vigilant and cognisant of the risks. Remaining data-driven in our approach, vigilant to unexpected shifts in prices and ready to act when necessary is essential for monetary policy. And in the wake of the remarkable levels of uncertainty, we should also maintain optionality in our policy tools and not locking ourselves into commitments that put our price stability objective at risk.

In the longer term, there is uncertainty around a number of factors that will affect inflation. For example, post-pandemic manufacturing chains could organise in a way that is more tolerant of higher costs, putting pressure on inflation. This could happen by means of partial reshoring or a shortening of the length of supply chains. This would mean tolerating higher cost structures in exchange for making the supply chain more robust to shocks. Looking even further ahead, shocks related to climate change are likely to play an increasing role for the outlook for price stability effecting its level, seasonality and volatility. Taken together these structural forces could coalesce to impact inflation but the path is not straightforward and is likely to be indirect. We do not yet know how these forces will progress and their impact on inflation remains ambiguous. It is also difficult to know to what extent these forces will tip the balance away from the structural forces that had kept inflation low for so long until recently.

The Irish outlook

While price stability is the goal of central banks, our monetary policy actions to achieve this goal do not take place in a vacuum. I have discussed the importance of interactions between monetary and fiscal policy previously. Fiscal policy is particularly important for countries in a currency area (like the euro area) who have less scope to use monetary policy to counteract shocks that may only affect their own economies, or common shocks that are experienced more intensely in some Member States than others. For Ireland – a small open economy in a monetary union – this is all the more important, as building resilience through prudent fiscal policy in good times creates the necessary capacity to respond to shocks that affect our economy.

Government decisions on expenditure and tax revenue can have an important impact on economic growth, inflation and the broader economy and labour market. The effect of the fiscal stance on the economy will be influenced by a range of factors, in particular whether the economy is operating above or below its estimated long-run potential as well as conditions in the international economy. In this context, it is worth briefly reviewing our latest economic assessment, set out in our most recent Quarterly Bulletin last month. In brief, the Irish economy is recovering swiftly, and domestic economic activity is expected to reach its pre-pandemic level by the end of this year. Further growth is expected over the next two years with the unemployment rate projected to fall to below 6 per cent by 2023. The economy is likely to be closer to full capacity than the euro area average and we are forecasting strong growth which could result in further inflationary pressure.

It is against this backdrop that the fiscal policy stance in Budget 2022 was set. In line with the new expenditure rule announced in the Summer Economic Statement10, the forecasts in Budget 2022 indicate that overall growth in core government spending is expected to be limited to 5 per cent per annum from 2023-2025 (the estimated long-run potential growth rate of the economy). Within this, and as reflected in the recently published National Development Plan, public investment as a proportion of national income (GNI*) is forecast rise to over 5 per cent by 2024. This would bring public investment to its highest level since 2008 and well above the average for the euro area.

While action is needed to address infrastructure deficits in housing and meet the challenges of climate change, given the current economic backdrop, any investment needs to be managed carefully and accompanied where necessary by structural reforms to ensure the demand it generates does not lead to excessive inflationary pressures. Recent developments reinforce the need for caution. There is evidence of supply chain bottlenecks and energy prices putting upward pressure on input prices and output prices across the manufacturing, service's and construction sectors.11 If sustained, increases in prices through these channels are likely to spill over to domestic prices and costs with some tentative signs of this occurring in certain sectors. For instance, there is evidence of a pick-up in price pressures in the construction sector with tender prices increasing by 7 per cent in the first half of 2021.12 Moreover, labour market conditions have improved markedly, as employment rebounded sharply in Q2 2021. There are large numbers of job openings in specific sectors – including construction – and unemployment has declined faster than our expectation earlier in the year, albeit still above pre-pandemic levels.

In an environment where supply-side constraints are already creating inflationary pressures, further stimulating demand through additional increases in current or capital expenditure beyond existing plans would likely exacerbate price pressures, driving a wider gap between nominal and real growth in economic activity. Over a prolonged period this could undermine competitiveness and result in the emergence of imbalances, including in the form of some crowding-out of the traded sector. As outlined in Central Bank research, one way to reduce the risk of increases in current expenditure adding to overheating pressures is to ensure that such expenditure is funded by increases in revenue rather than debt.13 This can deliver the dual benefits of demonstrating the sustainability of permanent current spending increases while at the same time creating space for the planned increases in public investment.

Put simply, the economy as a whole does not need, nor would it benefit from, expansionary fiscal policy in the coming years. More generally, as a small open economy in the euro area, fiscal policy has an enhanced role in Ireland as the main instrument of macroeconomic stabilisation. The stance of euro area monetary policy during the pandemic – a common shock albeit experienced to different magnitudes across countries – has been helpful to the Irish economy and public finances in helping to maintain favourable financing conditions for households, firms and the government. Since the ECB’s monetary policy stance is set in order to achieve the price stability objective according to conditions across the entire euro area, there is always the possibility that in future it may not fully align with conditions in the Irish economy, as was the case in the early 2000s when domestic drivers of inflation were more dominant. This underpins the importance of using countercyclical fiscal policy to manage the economic cycle and avoid the build-up of economic imbalances. This in turn is necessary in order to build economic resilience so that domestic policy can respond to shocks in the future. Macroprudential policy, which is in place to safeguard the capacity of the financial sector to absorb rather than amplify shocks, also contributes to broader economic resilience.

While the economy as a whole may not need a fiscal expansion, it does not mean that targeted measures both to increase the long-term and short-term welfare of Irish households cannot be undertaken. Indeed, creating the space for the necessary investment in housing and climate action will be important to improving the economic welfare of households and businesses. Likewise, targeted measures that aim to offset the negative impact that current inflation has on vulnerable households with lower incomes can be achieved without adding to excess demand at a macro level.

Conclusion

One thing that is clear among all the uncertainty is that the pandemic’s consequences are still being felt across the Irish and euro area economies. We know the reasons underlying today’s inflation. We believe that those reasons mean today’s inflation is not going to be permanent but I accept that we do not know that to the same degree: the economy may respond in ways we do not expect. But the judgement that an immediate monetary policy response is not warranted – that patience is an important and worthwhile virtue – is reasonable and in the present circumstances correct. However, I also believe that monetary policy should be prepared to respond if the evidence starts to point to a need for this earlier than we had expected. When the evidence changes, we should not hesitate to change our approach.

We have the tools to support the economy and the tools to deliver price stability. We did not hesitate to take the necessary steps at the start of the pandemic and we should not hesitate to take the necessary steps at its end. Maintaining vigilance and optionality remain important parts of our toolkit so that we can deliver price stability to all citizens in the euro area.

1On the occasion of the publication of the Economic Letter, An overview of recent inflation developments (PDF 630.96KB) by David Byrne and Zivile Zekaite.

2Byrne, D., and Zekaite, Z., 2021. An overview of inflation developments. Central Bank of Ireland, Economic Letter, Vol. 2021, No.7.

3Byrne, S., Scally, J., and Zekaite, Z., 2021. Drivers of Recent Inflation. Central Bank of Ireland, Quarterly Bulletin 4: Box E, October 2021.

4Makhlouf, Gabriel. Governor’s Blog: Introduction. Governor’s Blog, April 2020.

5October 2021 HICP. Pre-pandemic comparison made with respect to October 2019.

6This static approach to estimating household-specific inflation does not consider potential changes in demand due to higher prices. For example, if high fuel costs shift demand away from own personal transport to public transport.

7Makhlouf, Gabriel. Monetary policy and interest rates in Ireland. Governor’s Blog, December 2020.

8Having a good quality measure of inflation can be challenging. Ensuring it captures changes in the quality of goods and service's that can evolve is not easy. Similarly, new, innovative goods and service's are replacing old ones at much faster rates, which makes measurement over time more difficult. The growth of online shopping, where prices may differ from those in local shops, also makes measuring price changes more complex.

9Recent ECB research (Dossche et al. 2021) shows that the lower income households’ income is up to three times more sensitive to changes in GDP growth compared to higher income households, changing by 1.5% for each 1% change in GDP growth.

10Summer Economic Statement 2021, Department of Finance, Department of Public Expenditure and Reform, July 2021.

11See Purchasing Manager Indices for Manufacturing and Service's here, and for Construction here.

12Tender Price Index (PDF 2.19MB), Society of Chartered Surveyors Ireland, October 2021.

13Conefrey, T., Hickey, R., and Walsh, G., 2021. An Analysis of Medium-Term Risks to the Public Finances. Central Bank of Ireland, Economic Letter, Vol. 2021, No.6.