Women in economics: how can we accelerate progress? - Remarks by Vasileios Madouros, Deputy Governor, Monetary and Financial Stability

05 September 2024

Speech

Good morning everyone.1

It is a real pleasure to welcome you all here for today’s conference on Gender, Economics and Society.

Let me start by expressing my gratitude to the Irish Society for Women in Economics (ISWE).

Not only for organising today’s conference, but – most importantly – for your continued efforts to empower, inspire and increase the visibility of women in economics in Ireland.

Gender diversity in the economics profession is an area that matters for public policy in Ireland as a whole. And it is particularly relevant for us, at the Central Bank, given our mandate and mission.

So I thought I would use this opportunity to cover our own journey towards greater gender diversity, and some of the challenges we still face, with a focus on economics.

Women in economics: where have we got to?

Before I turn to the Central Bank, let me start with the broader context of the profession.

It is clear that women continue to be significantly under-represented in economics.

This is a global pattern and, unfortunately, one that has proved to be particularly persistent over time.

We can see that through differences lenses.

Women are under-represented in the study of economics

Although precise definitions vary, in the US, the UK and Ireland women account for only around 1 in 3 of undergraduate students of economics.2

Women economists are under-represented in academia

In the US, women account for around 1 in 5 of full professors in economics, in the UK for around 1 in 4 and in Ireland around 1 in 3.3

Women economists are under-represented in the private sector

The share of women employed as chief economists in large, global banks was around 26% in 2023. In large, global insurers, it was around 7%.4

Women economists are under-represented in the public sector.

Globally, only about 12% of central bank governors were women in 2023, and only around 16.5% of ministers for finance.5

In Ireland, we have not (yet) had a woman serving as either central bank governor or minister for finance.

These are striking facts.

Of course, if one were to look at equivalent statistics two or three decades ago, they would have pointed to even lower levels of representation.

So there has been meaningful progress – which is very welcome. But we have much further to go to strengthen gender diversity within the profession.

And – for me – there are two areas that merit particular attention.

First, there are some signs that beg the question of whether progress towards greater gender diversity in the profession may be stalling in some dimensions.

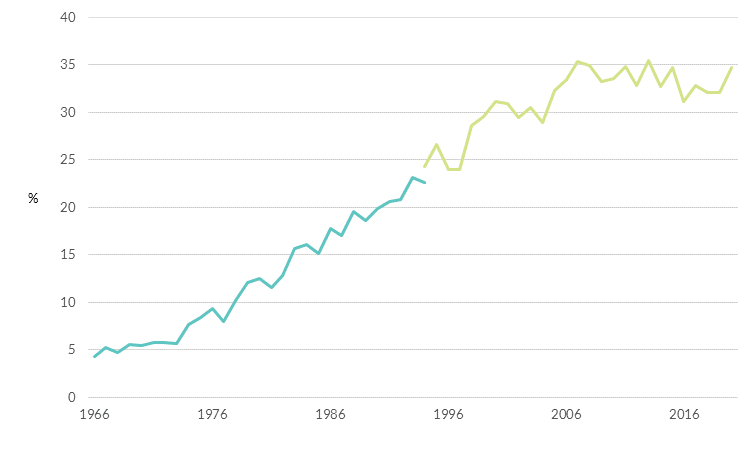

For example, in the US, the share of women receiving an economics PhD rose steadily from about 5 per cent in the 1960s to around one-third in the mid-2000s.

Since the mid-2000s, though, the share of new economics PhDs awarded to women has been broadly stable at that level (Chart 1).

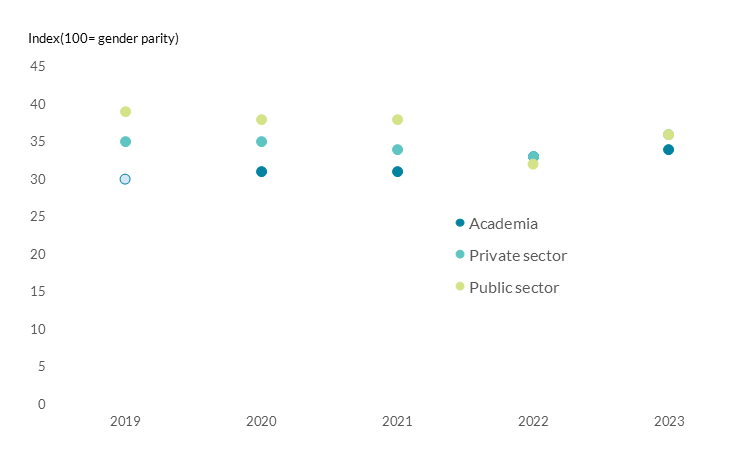

A broader lens to monitor progress is the extent of women’s representation across leadership positions in economics – whether in academia, the private or the public sector.

In the five years since the global Women in Economics index was developed in 2019, it has not shown any discernible improvement (Chart 2).

And, in Ireland, the share of female students sitting higher level economics for their leaving cert has fluctuated at around 35% since 2011, with no evidence of the gender gap narrowing over time.

Chart 1: The share of new economics PhDs awarded to women in the US appears to have plateaued

Source: Meade et al (2021) ‘Changes in Women's Representation in Economics: New Data from the AEA Papers and Proceedings’, FEDS Notes.

Chart 2: There has been no visible upward trend in the Women in Economics index in the 5 years to 2023

Source: Various editions of the Women in Economics Index, available here.

Note: The methodology for academia in the index was adjusted in 2020. The metric for 2019 has been adjusted to enable a better like-for-like comparison.

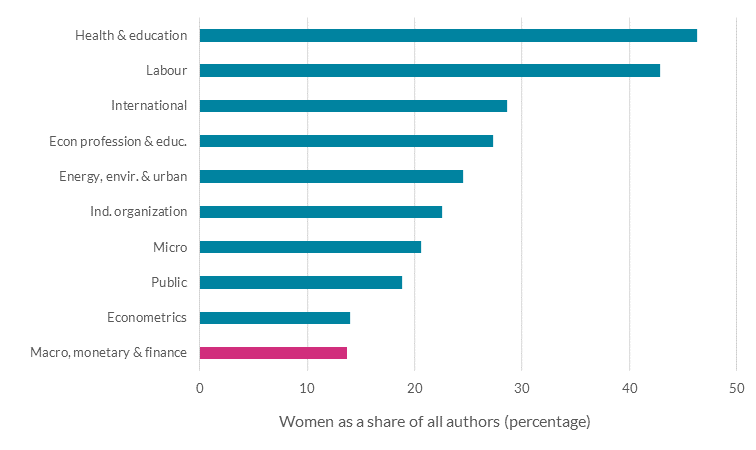

Second, the representation of women is not homogeneous across different fields of economics.

Indeed, under-representation of women in macro-finance is particularly pronounced.

For example, between 2011–20, women represented only 14 percent of authors of AEA papers in macroeconomics, monetary economics, and finance (Chart 3).

A similar pattern is evident in the share of women specialising in macro-finance at PhD level.6

This is particularly relevant for us at the Central Bank, as macro-finance is a field of economics that is very closely related to our own mandate and mission.

Chart 3: The under-representation of women as authors in macro-finance papers is particularly pronounced

Source: Meade et al (2021) ‘Changes in Women's Representation in Economics: New Data from the AEA Papers and Proceedings’, FEDS Notes.

Notes: Women as a share of all authors, by paper’s research field, 2011-2020.

The costs of under-representation in economics and central banking

The continued under-representation of women in economics – and institutions that employ economists, including central banks – entails important costs.

Why?

Because it can limit diversity of thought. And, in doing so, it can hinder our collective ability to tackle complex problems effectively, increasing the risk of blind spots, biases and groupthink.

The evidence – from a range of disciplines – is clear. Diverse teams and organisations are much better equipped to tackle complex problems.7

The basis for that is cognitive diversity. That is differences in how people think, how they perceive information and how they analyse it.

Diversity of thought results in teams and organisations that are better able to innovate, solve problems and make predictions.

In turn, cognitive diversity is influenced by identity diversity. That includes differences in gender, ethnic background, sexual orientation, education, age or ability.

These dimensions of our identity directly influence our life experiences and – in turn – shape our perspectives and our way of thinking.

This is very relevant to the economics profession.

The economy and financial system are prime examples of complex systems.

So diversity of thought is essential for our collective ability to understand these complex systems and to tackle difficult public policy problems.

And – consistent with the broader evidence – gender diversity adds to diversity in thinking in economics.

For example, research in the US and Europe has shown that – controlling for a range of factors – there are important differences between the views of male and female economists.8,9

Overall, then, the continued under-representation of women in economics means that the profession is likely missing out on perspectives and ideas.

Perspectives and ideas that matter for public policy and, ultimately, for people – now and into the future.

The Central Bank’s own journey

Let me now turn to our own journey, at the Central Bank.

Like many other organisations, in Ireland and globally, representation of women at the Central Bank was held back by a range of explicit and implicit barriers over the course of our history.10

These included, of course, the marriage bar, under which – until as late as 1973 – legislation required women in the public sector to resign from their job when they married.

They also included a range of organisational barriers in the first few decades of our existence.

For example, until the 1970s, many women in the Bank would have belonged to female-only grades of employment, such as lady clerks or writing assistants.

Indeed, competitions for roles in the Central Bank – like the broader public sector – were often advertised by gender.

Fast-forward to where we are today, and the picture is – thankfully – radically different, amid a broader societal transformation.

In the Central Bank as a whole, women now account for around 49% of our people.

Our mean gender pay gap is now 3.9% in favour of male employees. This compares with a State-wide mean gender pay gap in favour of male employees of around 9.6% in 2022.

But we are still not where we need to be.

Let me focus on two areas in particular.

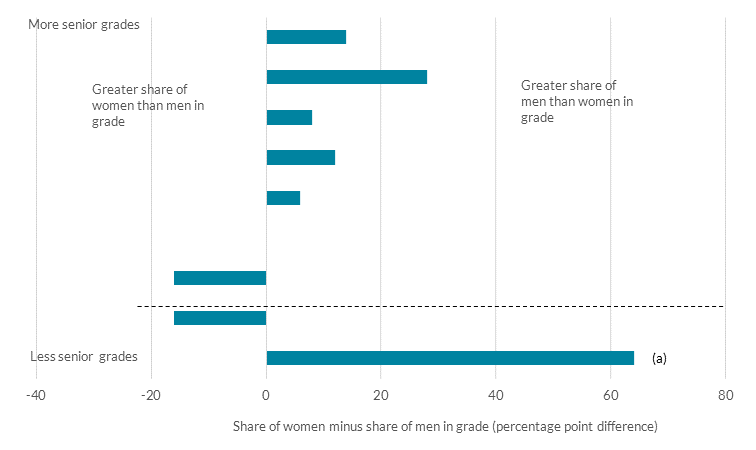

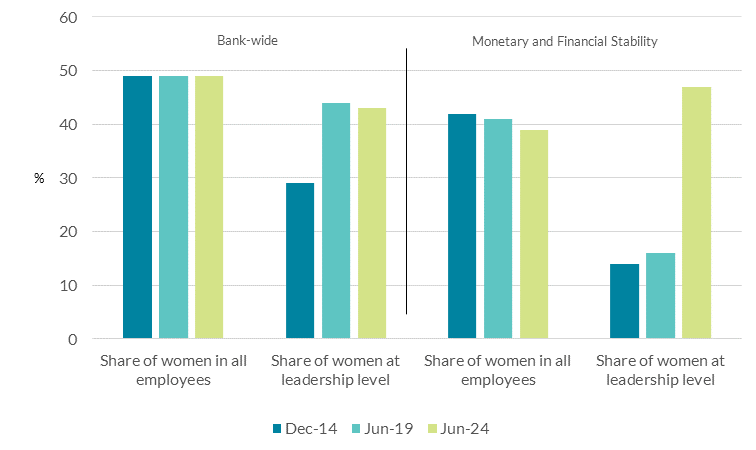

First, when we look at the representation of women by grade, women are still underrepresented in more senior positions (Chart 4).

Chart 4: Women are still under-represented in senior grades at the Central Bank

Source: Central Bank of Ireland.

Notes: Percentage point difference between the share of women and men employees at the Central Bank, by grade.

The bars above the line reflect the ‘Professional and Administrative’ job bands. The bar below the line reflects the Technical and General (T&G) job band.

This pattern is a key factor in explaining the remaining gender pay gap.

This, of course, is better than where we were in the past. It feels hard to believe now, but the first appointment of a woman as a Head of Division was as recently as 2001.

So we have further to go to achieve our goal that our senior leadership population is made up of at least 45% of males and females.

Second, let me zoom in on economics in particular.

Some of you might think that the Central Bank is full of economists. In practice, this is not the case.

The Central Bank is unusual in terms of the breath of our mandate, covering monetary policy, financial stability, prudential and conduct regulation as well as resolution.

So we employ a range of experts, from a range of fields.

Economic expertise tends to be concentrated in a relatively small part of the Bank, which performs those functions that are most typically associated with a ‘stand-alone’ central bank.11

And in that part of the Bank there is a greater gender imbalance, compared to the rest of the organisation.

While at a Bank-wide level, women account for around 49% of our people, in the part of the Bank that typically employs more economists, the equivalent share is around 39% (Chart 5). And that share has actually fallen marginally over the past decade.

More positively, in that same part of the Bank, there has been a significant increase in the share of women in leadership positions over the past decade (Chart 5).

This has been a big change, and one that – amongst others – means that more junior women colleagues can see themselves more clearly in senior positions.

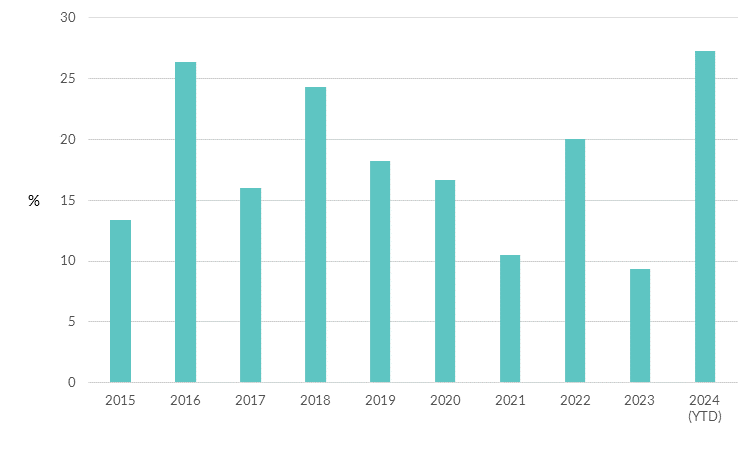

Another metric is the share of authors of our working paper series, largely written by economists.

This is volatile, because of relatively small numbers, but – overall – there has not been any discernible trend over time (Chart 6).

In summary, while the Bank has made substantial progress towards greater gender diversity over time, we still have further to go, especially in the part of the Bank where economic expertise is concentrated.

Chart 5: Share of women in the Bank and the area of the Bank that typically employs more economists

Source: Central Bank of Ireland.

Notes: The area of the Bank that typically employs more economists is ‘Monetary and Financial Stability’, which is more closely associated with traditional central banking functions. Leadership refers to Heads of Division and above, as per the definition in our gender representation goals.

Chart 6: Women’s share of authorship of the Central Bank’s working paper series over the past decade

Source: Central Bank of Ireland.

Our approach to strengthening diversity and inclusion in the Central Bank

Our values as an organisation are clear: "We embrace diversity and inclusion, as they strengthen us, as individuals and as an organisation".12

So how are we putting those values into action?

Over the past decade, we have taken a more intentional and strategic approach to diversity and inclusion (D&I).

This includes a focus on gender balance, but it is not limited to that. There are many different dimensions to diversity, and they are all important to ensure that we reflect the society that we serve.

Our strategy has been multi-faceted.

We have focused on leadership.

That has been partly by appointing a sponsor for D&I at an executive level. Because demonstrating commitment at the highest levels of the organisation is a necessary step to make progress.

We have also designed bespoke training on inclusive leadership for all of our leaders.

Again, this is because leadership is critical and – for the organisation to become truly diverse and inclusive – visible actions and behaviours need to start at the top.

We have put in the resources.

We have set up a central D&I team. Because if you want to be serious about change, you need to resource it.

The team is an enabler for the rest of the organisation, working closely with business areas right across the Bank to deliver our D&I strategy and action plans.13

We have initiated targeted changes to our practices.

Examples include enhanced training for our hiring managers, including with a D&I lens, or requiring mixed interviewing panels.

Because recruitment is a key dimension for attracting diverse talent.

But recruitment is not enough. Developing diverse talent is equally important, so this has also been a key area of focus for us.

For example, we have invested in our internal mentoring programme, where currently 70% of mentees are women, along with 51% of mentors.

And, since 2023, we have invested in supporting our emerging female leaders to develop through an external ‘Women in Leadership’ programme.

We have grown our employee networks.

A key element of our strategy is an appreciation that we need to understand better the frictions or barriers faced by different under-represented groups.

And the best way of understanding is listening to those with the lived experience.

That is why our five employee networks are central to our overall strategy of becoming a more diverse and inclusive organisation.

We have focused on measuring progress.

We are now collecting better data on the make-up of our organisation, although there are still gaps we need to fill.

We are using that data to measure progress, including against the representation goals for gender and disability that we introduced for the first time in 2020.14

And we are also using it to understand, analyse and act to address the underlying factors that are contributing to under-representation.15

We have also sought external benchmarks as part of our measurement of progress. For example, we have been assessed under the ‘Investors in Diversity’ framework by the Irish Centre for Diversity.

We recently moved up from ‘Bronze’ to ‘Silver’ under this framework, which is a positive indicator of progress, but also shows that we have further to go.

Focusing on women economists

These have all been important changes.

If I am honest, though, I don’t know if they will be sufficient to address the under-representation of women in those parts of the Bank where economic expertise is concentrated.

Or whether we need more targeted – and more creative – initiatives to really shift the dial, especially given the persistent trends we observe across the profession.

I do not have the answers to this today. But I can tell you that we are determined to make progress.

And we are open to ideas: whether tried-and-tested ideas that have worked in similar organisations, or newer ideas that we might want to consider.

What is also clear from the evidence is that the gender imbalance cuts across the economics profession: in academia, the private sector and the public sector.

It also starts early in the career trajectory, as well as gradually deteriorating over time, with evidence of a ‘leaky pipeline’.

So a co-ordinated approach is needed, across the profession, and one that also incorporates early interventions.

Which is one of the reasons why I am so grateful for the initiatives that ISWE has launched. And delighted to be lending our support to their endeavour.

Indeed, some of the more recent initiatives – such as the introduction of the ISWE mentoring programme or engagement with potential future talent in schools – have the potential to be powerful levers.

I believe that ISWE can act as a spark that helps us all accelerate progress, by fostering a more gender-balanced and inclusive profession.

But shifting the dial on the representation of women in economics is a collective responsibility, for all of us in the profession.

And, as one of the largest participants in the labour market for economists in the State, we take that responsibility very seriously.

Thank you very much for listening and I hope you enjoy today’s conference.

[1] I am very grateful Tara McIndoe, Patrick Haran, Kevin Mahon, Micheal O’Leary, Lucia Bermejo Rey, Pedro Velho de Sa and Caroline Mehigan for their advice and assistance with putting together these remarks.

[4] See Schuetz et al (2024) ‘The Women in Economics Index – Monitoring Women Economists' Representation in Leadership Positions’, DIW Berlin Discussion Paper, no 2076.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Sierminska and Oaxaca (2021) ‘Gender Differences in Economics PhD Field Specializations with Correlated

Choices’, IZA Discussion Paper, No. 14778.

[7] For a comprehensive review of both the theory and evidence, see Page (2017) ‘The Diversity Bonus’, Princeton University Press.

[8] May et al (2014), ‘Are Disagreements among Male and Female Economists Marginal at Best?: A Survey of AEA Members and Their Views on Economics’, Contemporary Economic Policy 32 (1): 111–32.

[9] May et al (2018) ‘Gender and European economic policy: a survey of the views of European economists on contemporary economic policy’, Kyklos 71: 162–183.

[10] The material on the first few decades of the Central Bank is based on Dr. Deirdre Foley’s insightful talk on ‘Women in Banking at the Central Bank of Ireland’, delivered during the 2023 Dublin Festival of History.

[11] This refers to the ‘Monetary and Financial Stability’ area of the Bank.

[12] See Central Bank of Ireland (2021) ‘Our Culture Statement’.

[15] Given that we are one of the biggest employers of economists in the State, we have also shared our data to support studies on women in economics in Ireland as a whole. See, for example, Devereux and Samahita (2022) ‘Gender, Productivity and Promotion in the Irish Economics Profession’