Remarks by Director of Markets Supervision, Gareth Murphy, at the International Centre for Business Information Forum 2014

30 September 2014

Speech

Good afternoon ladies and gentlemen.

I would like to thank the organisers of this inaugural conference on private equity for inviting me here to speak today.

In my remarks, I will spend a little time

-

recalling the evolution of the private equity industry over the last decade; and

- reflecting on the economic role that private equity plays for firms seeking funding and for investors.

Before I do so, let me take a few moments to reflect on regulatory developments in the world of alternative investments over the last few years.

Private equity and AIFMD

Some of you will remember the conference on Private Equity and Hedge Funds hosted by the European Commission back in February 2010 which marked the early stages of the consultation process on AIFMD. The Internal Markets Commissioner at the time, Mr. Charlie McCreevy, made an instructive remark: "Hedge funds. Private equity. Different industries. Different policy concerns. But part of the same political agenda." And so it proved.

When viewed from a distance, financial services regulation is ultimately a political construct. It is initiated by the European Commission and decided on by elected politicians in the European Parliament and the European Council. After that, regulators work to interpret and implement these new rules 1. And regulators are accountable to parliaments for the execution of their mandates and even, in some cases, for approval of their budgets.

Realpolitik determined that AIFMD should deal with both hedge funds and private equity. Mr McCreevy's call for a 'suitably differentiated response' to the issues posed by hedge funds and private equity was overtaken by the political drive to regulate these two sectors: once and for all and all at once.

In this substantial and complicated directive which imposes some 169 obligations on the alternative investment fund manager (AIFM), there are some common elements which are focused on both the hedge fund and private equity industries, such as:

- capital requirements;

- monitoring and control of leverage;

- regulatory reporting requirements;

- a European passport for management and marketing, and

remuneration.

Some of the contentious rules are more relevant for one industry than the other.

For example, the strict liability on custodians and the associated asset segregation rules are more relevant to hedge fund managers 2. Likewise, the rules around acquisitions and asset-stripping are clearly more focused on private equity fund managers 3.

Whilst many in industry would regard AIFMD as somewhat of a curate's egg, I would highlight two elements of the directive which are significant.

Regulatory reporting

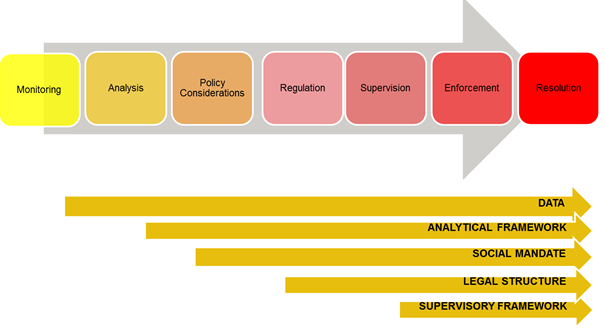

Data collection is the key pillar supporting successful and proportionate regulatory engagement 4. It supports the spectrum of regulatory engagement which spans monitoring, analysis, policy-formation, rule-writing, supervision, enforcement and resolution.

AIFMD regulatory reporting will enable financial authorities to efficiently monitor the alternative investment fund industry from a micro-prudential perspective whilst also providing a framework for mapping the risks of the financial system as a whole. In a world where various consumer and technology industries have mastered the use of data about their customers, it is entirely right that regulatory reporting is part of an effective and cost-efficient supervisory strategy.

That said, one might question the approach which was taken to set out the content of the reporting requirements in Annex IV of the Commission delegated act as opposed to mandating it to ESMA. Had the latter approach been adopted, there would have been more scope to refine the list of data sought and also to add to it on an iterative basis over time as regulatory uses of it evolve. And the powers that do exist to gather additional data apply at a national level and do not lend themselves to co-ordinated action 5.

On a separate matter, there is a misalignment between the reporting frameworks in the US and EU on two levels. First the content is different – and I know that this is a source of frustration for the industry. Second, unlike ESMA, the US Securities and Exchange Commission can change Form PF.

AIFM Passport under Articles 32 and 33

The second significant element of AIFMD which I would like to mention is the AIFM passport. Since the passing of the July 22 deadline, when the transition period for AIFMD ended, my colleagues at the Central Bank have processed 46 inward notifications. And that is just a fraction of the passporting activity at the European level. So AIFMD does have the potential to strengthen the single market. This contrasts with the experience of UCITS IV where the management passport has been less popular.

My interactions with some small but significant third country regulators suggest that AIFMD is likely to set a standard for hedge fund regulation in some jurisdictions outside of Europe since Europe is simply too important a market to ignore. Clearly, there will be eager anticipation of ESMA’s advice in relation to the extension of the passport to third countries 6. Work is well under way at ESMA’s Investment Management Standing Committee on this issue. It would not be appropriate to pre-empt the outcome of this work but suffice to say, there are very significant issues at play covering mutual access to investment markets and equivalence of regulatory and supervisory standards.

Before looking ahead to future regulatory developments, it is worth taking a step back and considering the raison d’être for private equity.

Growth of the private equity industry

| Year |

Private Equity AUM

|

Global Financial Assets |

PE AUM as a % of Global Financial Assets |

| 2000 |

$716 billion |

$119 trillion |

0.6% |

| 2005 |

$1238 billion |

$165 trillion |

0.75% |

| 2006 |

$1704 billion |

$185 trillion |

0.92% |

| 2007 |

$2276 billion |

$206 trillion |

1.10% |

| 2008 |

$2279 billion |

$189 trillion |

1.21% |

| 2009 |

$2480 billion |

$206 trillion |

1.20% |

| 2010 |

$2776 billion |

$219 trillion |

1.27% |

| 2011 |

$3036 billion |

$218 trillion |

1.39% |

| 2012 |

$3273 billion |

$225 trillion |

1.45% |

Source: Private Equity AUM from 2014 Preqin Private Equity Performance Monitor.

Global Financial Assets data from McKinsey Global Institute Analysis (2013) “Financial globalization: Retreat or reset?” Global capital markets 2013 report.

The evolution of the industry is neatly summarised in the following chart which shows considerable growth over the twelve years since 2000. The stock of private equity assets more than quadrupled to approximately $3.25trn. Measured against the global stock of financial assets which doubled over the same period to approximately $250trn, we can see that private equity is becoming a more significant channel for investment finance to the global real economy.

Apart from the underlying economics of private equity, there are two conjunctural reasons underlying the growth in private equity in recent years.

Owing to the global financial crisis, the supply of finance from parts of the banking system has slowed down and in some cases reversed.7 Therefore, the market has sought to explore alternative channels of finance, including private equity.

On the investment demand side, the protracted period of low nominal and real interest rates has led to a search for yield across all asset classes. It should come as no surprise that flows into private equity funds have been increasing during this period. 8

But leaving these points aside, it is important to answer the question: "why does private equity exist"?

Financing the real economy

Notwithstanding the differences between different forms of private equity investment, I see three significant economic arguments which support its existence:

- Taking a company public is an expensive business. There are significant public disclosure obligations on issuers as part of the initial public offering (IPO) process (these arise from the Prospectus Directive, Transparency Directive, Market Abuse Directive and exchange listing rules). In addition, a successful IPO requires a supporting ecosystem of analysts, advisors, brokers and underwriters, all of which need to be paid. These costs fall on (a combination of) the issuer and the investor. Thus private equity offers a less expensive form of equity-based financing. As an aside, you will note that legislators have made attempts via MiFID II to promote SME finance by allowing multi-lateral trading platforms (MTFs) to operate specially designated 'SME Growth Markets' with lower costs and requirements than a full listing would require 9. But the latest discussion about a Capital Markets Union suggests that this work is incomplete and further developments are in prospect.

- The burden of public equity disclosure obligations has been said to lead to short-termism on the part of company management. It has been said that "too much liquidity and information unlocks the impatience gene" 10. In contrast, private equity, by design, requires investors to accept less frequent pricing and fewer redemption possibilities. Having longer investment horizons can take pressure off management to meet short term performance targets and allow a focus on the medium to long-term strategy of the business.

- Whilst commercial bank loans support firms in their nascent stages, at a certain point in the evolution of a firm such bank loans may no longer be appropriate. Often firms require funding for projects for which the returns are uncertain and for which there may not be an asset linked to the project to offer as collateral. Private equity plays an important role funding these higher risk projects.

Leaving aside these arguments, there is academic literature which suggests that firms which are financed through private equity play an important role in supporting real economic activity whether measured by new business incorporation 11, innovation 12 or employment 13 metrics.

Private equity as an investment product

However, whilst it is important to highlight the positive role of private equity in financing the real economy, there is a mixed verdict on the relative performance of private equity as an asset for end-investors.

Some commentators suggest that private equity buyout fund returns consistently outperform other forms of private equity investment, as well, as other, alternative, asset classes 14. Other academic studies show that private equity funds earn gross returns that exceed the S&P 500, on average 15. However, there is evidence to suggest that private equity limited partners may just break-even after adjusting for risk and illiquidity when total product fees (which include management fees and performance fees to the general partner) are accounted for 16. Indeed, some studies also note that the net return (after fees) is lower than an index-tracking portfolio, such as the S&P 500 average returns 17.

As we know from the debate on PRIIPs - or Packaged Retail and Insurance-based Investment Products which does not apply to non-retail investors in alternative investment funds - the issue of product fees is not confined to private equity funds but rather extends across the universe of investment products 18. These new requirements will build on the 'Key Investor Information Document' (KIID) developed under UCITS IV and include disclosures on product fees.

The key question which I would pose is whether the disclosures around product fees are sufficient to prompt a better risk- and liquidity- pricing of investment products vis-a-vis passive portfolio products.

Moreover, when considering private equity as a financing channel another question must be asked: could the level of product fees be constraining the efficient flow of capital to entrepreneurs in the real economy?

Financing the European economy

In the last 5 years, over 60 pieces of financial services legislation have been passed by the Council and Parliament. Initially, the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis drove the agenda 19. In recent years, the post-crisis policy discussion has shifted focus towards the financing of the European economy. The European Commission has consulted at length on the options for long-term finance in the European economy and has highlighted the importance of allowing a variety of channels to work in tandem to finance the equity and debt capital needs of the real economy.20 The creation of three new fund types dealing with venture capital, social entrepreneurs and long-term investment is an attempt to bridge that gap between certain specific sources of savings and targeted financing needs of the real economy.21

As a major European funds regulator, we have spent a considerable amount of time at the Central Bank of Ireland considering another aspect of this issue, namely, private debt.

The European Long-Term Investment Fund - or ELTIF, for short - has the potential to be a significant innovation in the development of the European market finance industry. My reading of current drafts of ELTIF under consideration is that this elective regime will, amongst other things, allow funds to originate loans.

The Central Bank of Ireland launched a discussion paper on loan origination by investment funds, fourteen months ago.22 This was a deliberate and considered attempt to explore solutions to meeting the credit needs of the real economy whilst carefully considering the issues of investor protection and financial stability. It is important that the risks of investor runs, misaligned incentives and mis-priced credit are addressed. In the downswing of a credit cycle, mis-priced credit may lead to an excessive number of bankruptcies and their associated deadweight costs on the economy23.

In the last few weeks, the Central Bank has removed a previous prohibition on loan origination by investment funds and created a carefully calibrated regime where all the necessary elements for prudent lending can take place and where institutional investors have another channel to finance the real economy.

Conclusion

As regulators, our focus is on investor protection, market integrity and financial stability. Ultimately, these support the economic purpose of the financial services industry including the alternative investment management industry. A level playing-field in Europe (and globally) is a necessary condition for the fulfilment of these goals.

AIFMD progressed the issue of regulatory reporting by hedge fund and private equity managers. This is consistent with a disciplined regulatory philosophy which seeks to use data to inform policy and supervision. Though it will take time, I am confident that the data which we are beginning to collect under AIFMD will improve the level of oversight of our financial system though the job of developing the reporting template should ideally have been given to ESMA.

The extension of the passport to non-EU AIFMs will herald another new departure in this far-reaching directive. Much will hinge on ESMA's advice to the co-legislators which is being prepared. There is still much to do. Yet another challenging and complex phase of AIFMD is underway.

As I touched on earlier, research suggests that private equity plays an important role in building and rebuilding businesses and in financing new innovation. It also indicates that the investment returns to the general partner are handsome but the return to the end-investors does not match passive investing in the stock market on a risk- and liquidity-adjusted basis. That should give us pause for thought. Is there a possibility that a moderation in product fees could encourage greater end-investor interest in private equity and private debt? And can the market achieve that fee moderation of its own accord?

Lastly, we look forward to the day when there is better alignment of regulation - including regulatory reporting - globally. But all of these noble initiatives require significant political commitment and a loud, constructive voice from industry.

On that note, I will pause there. Thank you for your attention. Have a good day.

References

Bain & Company (2014), “Global Private Equity Report 2014.”

Bernstein, S., Lerner, J., Sørensen, M., and P. Strömberg (2010), “Private Equity and Industry Performance,” NBER Working Papers 15632, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Central Bank of Ireland (2013), “Loan Origination by Investment Funds,” Central Bank of Ireland Discussion Paper, July 2013.

Davis, S.J., Haltiwanger, J.C., Jarmin, R.S., Lerner, J., and J. Miranda (2011), “Private Equity and Employment,” NBER Working Papers 17399, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

European Commission (2013), “Regulation (EU) No 345/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2013 on European Venture Capital Funds,” Official Journal of the European Union, April 2013.

European Commission (2013), “Regulation No 346/2013 of the European No 346/ 2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2013 on European Social Entrepreneurship Funds,” Official Journal of the European Union, April 2013.

EU Commission (2013), Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and the Council on European Long-term Investment Funds COM(2013) 462/2.

European Commission (2014), Commission Staff Working Paper Accompanying the document Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on Long-Term Financing of the European Economy, March 2014.

Ferran, E., Hill, J., Moloney, N., and J.C. Coffee (2012), "The regulatory aftermath of the global financial crisis", Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Haldane, A.G. (2010), “Patience and Finance,” speech given at the Oxford China Business Forum, Beijing, available at: http://www.bis.org/review/r100909e.pdf

Kaplan, S., and A. Schoar (2005), "Private Equity Performance: Returns, Persistence, and Capital Flows", Journal of Finance, August 2005

Lerner, J., Sorensen, M., and P. Stromberg (2011),"Private Equity and Long-Run Investment: The Case of Innovation," Journal of Finance, American Finance Association, vol. 66(2), pages 445-477, 04.

Moloney, K., and G. Murphy (2013), “The Spectrum of Regulatory Engagement,” Law and Financial Markets Review 7(3), June 2013.

Popov, A., and P. Roosenboom (2009), “On the real effects of private equity investment: evidence from new business creation,” Working Paper Series, European Central Bank 1078, European Central Bank.

Phalippou, L., and O. Gottschalg (2009), "The Performance of Private Equity Funds," Review of Financial Studies, Society for Financial Studies, vol. 22(4), pages 1747-1776, April.

Sorensen, S., Wang, N., and J. Yang (2013), "Valuing Private Equity," NBER Working Papers 19612, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

White, M., (1983), “The behavior of firms in financial distress”, Journal of Finance.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 The European Commission and the European Supervisory Authorities have amongst their responsibilities the task of ensuring the consistent application of these directives and regulations.

2 See 2011/61/EU Article 21

3 See 2011/61/EU Articles 26-30

4 See Moloney and Murphy (2013).

5 Article 24(5) does allow national competent authorities to gather further data but this is unlikely to happen on a co-ordinated basis without a strong consensus and a clear mandate to ESMA.

6 See 2011/61/EU Articles 67 and 68

7 See, for example, chapter two of Central Bank of Ireland (2013) for a brief overview of the academic literature on the impairment of the bank lending channel.

8 Bain & Company (2014).

9 See Art 35 of MiFID II.

10 Haldane (2010).

11 See Popov and Roosenboom (2009).

12 Lerner, Sorensen and Stromberg (2011) for example, find that in the years following PE buyouts, target firms do not noticeably change investment behaviour – proxied by the level of patenting activity – but that the number of citations does increase, perhaps indicating that PE owned firms pursue more influential innovations.

13 See Bernstein et al (2010) and Davis et al (2011).

14 See Gregory (2013)

15 See Kaplan and Schoar (2005)

16 See Sorensen, Wang and Yang (2013)

17 See Phalippou and Gottschalg (2009).

18 European Parliament. Report on the Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Key Information Documents for Investment Products (COM(2012)0352 – C7-0179/2012 – 2012/0169(COD)). Brussels: European Parliament, 2013. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?type=TA&reference=P7-TA-2014-0357&format=XML&language=EN (accessed 24 September 2014)

19 See Ferran, Moloney, Hill and Coffee (2012).

20 See European Commission (2014).

21 See 345/2013/EU (EuVECA), 346/2013/EU (EuSEF), and COM(2013) 462/2 (draft ELTIF proposal).

22 Central Bank of Ireland (2013).

23 See White (1983)