Managing the macroeconomic trade-offs of increased investment in infrastructure- Remarks by Deputy Governor Vasileios Madouros

03 October 2024

Speech

Good morning everyone.1

Thank you for inviting me to take part in this year’s conference.

Meeting infrastructure needs, now and into the future, matters for people and businesses across the country.

Earlier this year, the Central Bank’s Commission (our Board) held one of our regular meetings in Cork.

We used that opportunity to meet a number of businesses in the area, and hear first-hand about the economic issues that are high on their own agenda.

I remember asking one of those businesses about the challenges they faced. There was no hesitation in the response: “Infrastructure, infrastructure, infrastructure”.

This is a common theme expressed by companies operating in Ireland, whether domestic or foreign-owned.

From a public policy perspective, high-quality infrastructure is a necessary foundation for achieving long-term, sustainable growth.

It also plays a key role in determining quality of life and is an important enabler for ensuring that the gains of economic growth are shared broadly across the population.

So I thought I would use today’s remarks to cover some of the macro-economic aspects of infrastructure.

Current infrastructure needs

Let me start with the current economic context.

Despite a number of large external shocks in recent years, the economy has proved remarkably resilient.

The recovery in demand following the onset of the pandemic has been strong, driving a robust expansion in economic activity.

The size of the Irish economy, excluding globalisation effects, is estimated to have grown by 5% last year.

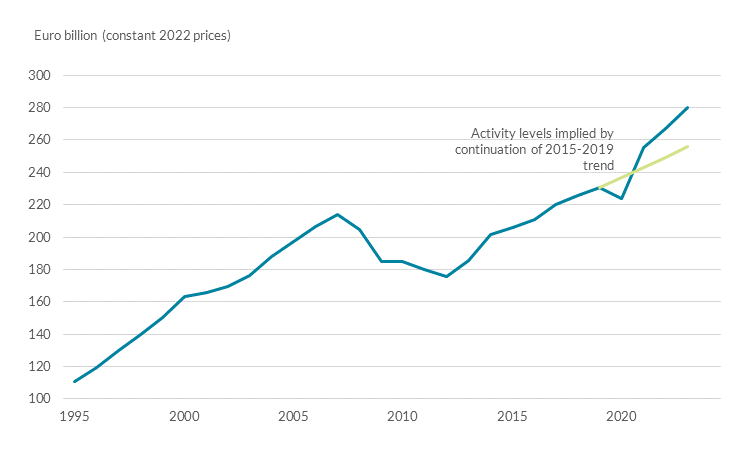

Indeed, real economic activity levels in 2023 were above what would have been implied by a continuation of pre-pandemic trends (Chart 1).

In that context, the labour market has performed strongly, with the number of people in employment reaching record highs.

And nominal household incomes have grown significantly, driven both by expanding employment and, more recently, nominal wage growth.

This strong momentum of demand, though, means that the economy has increasingly been facing capacity constraints.

These capacity constraints have been evident in the labour market.

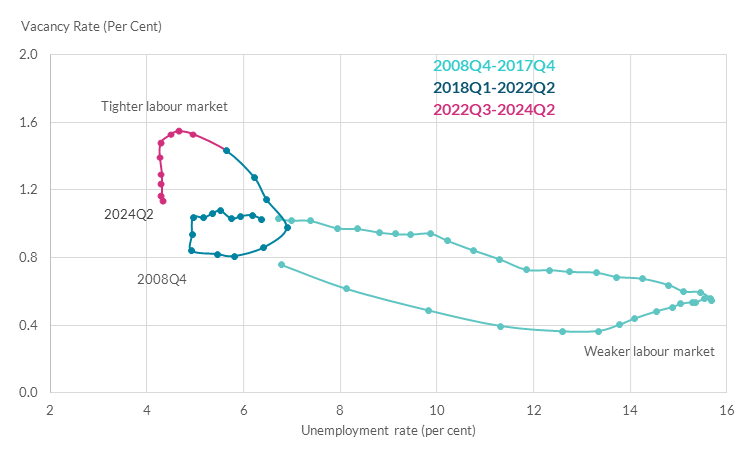

The past few years have seen a combination of historically low unemployment and a high level of vacancies (Chart 2).

Chart 1: Economic activity has exceeded pre-pandemic trends

Source: CSO.

Chart 2: Labour market imbalances have eased, as vacancies rates have fallen

Source: CSO.

While vacancies have eased more recently, pointing to a softening in demand for labour, conditions in the labour market remain relatively tight.

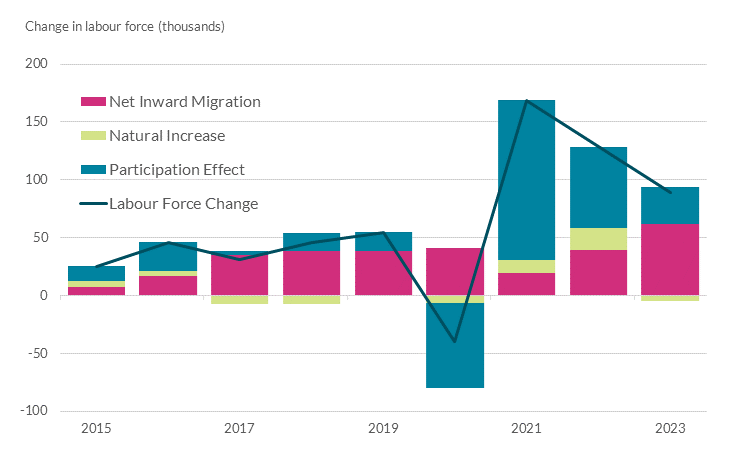

Two factors have acted as a ‘release valve’ to ease these pressures in recent years.

First, the unexpected and significant increase in labour force participation following the pandemic, especially amongst women.

Second, the significant level of net migration into Ireland, expanding the available pool of labour (Chart 3).

Chart 3: Net migration has contributed to the increase in the labour force

Source: CSO.

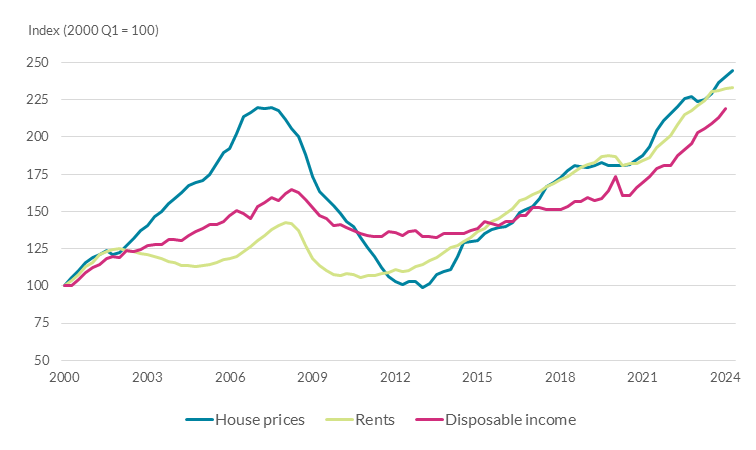

Chart 4: The imbalance between housing demand and supply has led to housing affordability pressures

Source: CSO.

While the inflow of labour from abroad has helped ease labour market pressures, supply-side bottlenecks have become increasingly evident in our infrastructure.

This is most clearly evident in the housing market.

A persistent mismatch between the demand and supply of housing has emerged over the past decade.

In turn, this has resulted in house prices and rents rising faster than incomes, stretching household budgets (Chart 4).

Infrastructure constraints are not just evident in terms of the number of homes.

Indeed, one of the underlying factors that determines the supply of housing is the availability of serviced land.

This relies on supporting infrastructure – water, sewerage, energy and transport – being available at sufficient scale, and in locations closest to housing demand.

In energy, EirGrid has been warning for a number of years of a growing tightness between supply and demand for electricity.2

In relation to water, Uisce Eireann has pointed to the need for additional investment to address supply deficits.

And, in transport, Ireland’s system is heavily reliant on roads and motor vehicles, with greater constraints on the infrastructure supporting public transport.

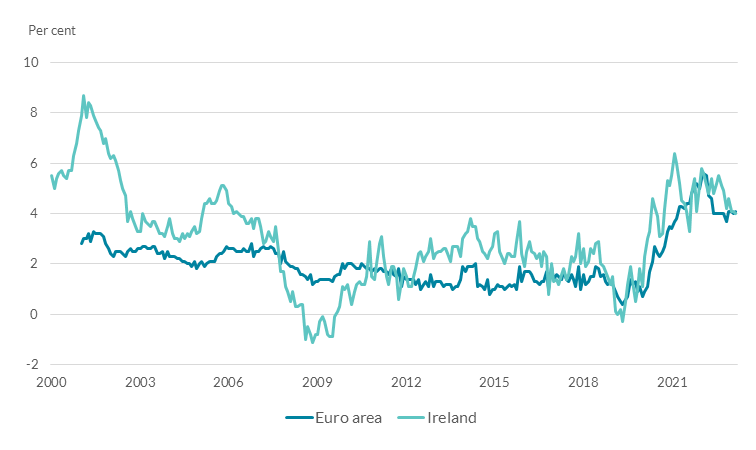

Chart 5: Services inflation remains elevated

Source: Eurostat.

Addressing these supply-side bottlenecks is critical for the sustainable growth in living standards.

Indeed, our own assessment is that such supply constraints are one of the factors that will weigh on the degree of economic expansion in the coming years.

And, if demand conditions in the economy evolve more strongly than currently expected, there is a risk that inflation will prove more persistent, with implications for competitiveness and living standards.

Headline inflation has fallen back significantly recently, in part reflecting the unwinding of the very large supply-side shocks we saw during the pandemic and the energy crisis.

But domestically-generated inflation – a reasonable proxy for which is services inflation – has been more persistent (Chart 5).

While this is a pattern that we see across the euro area, it is important that Ireland does not become an outlier with respect to domestically-generated inflation dynamics.

Structural transitions through an infrastructure lens

Beyond the current infrastructural constraints and the cyclical position of the economy, it is also important to look further into the future.

Indeed, given the multi-year nature of infrastructure projects, long-term planning is essential.

And, as we look ahead, there are a number of structural shifts that the (global as well as the Irish) economy will need to navigate.

Climate change and the transition to a low-carbon economy; an increasingly fragmented global economy; increased digitalisation and evolving demographics.

These structural shifts also have important implications for our infrastructure.

So let me cover each in turn, through an infrastructural lens.

Climate change and transition to net zero

Let me start with climate change and the path to net zero.

This is probably the transition that entails the most significant implications for our infrastructure into the future.

It is clear that there is a need to decarbonise our economy, to mitigate the threat of climate change.

Given the current dependence of the economy on carbon, the required changes are nothing short of a transformation.

The government has established the legal framework for Ireland to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

And an interim target of achieving a 51 percent reduction in emissions relative to 2018 by 2030.

Achieving Ireland’s emission reduction targets will require significant investment in adapting our infrastructure over the next decade.

From retrofitting our homes and offices, to transforming our energy system, to greening our transport network.

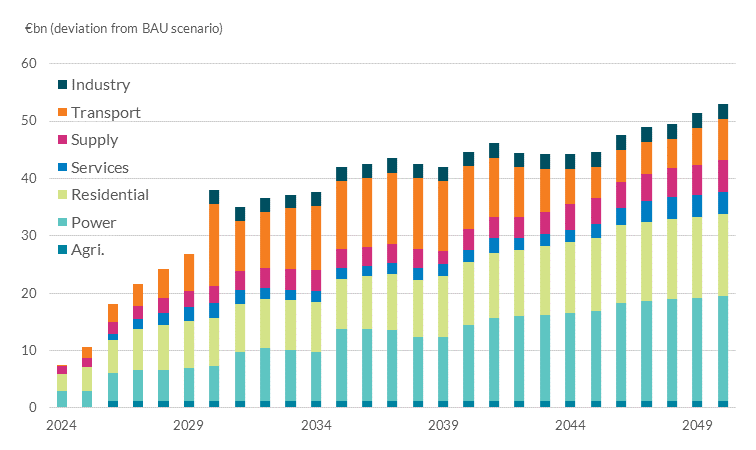

Estimates suggest that additional investment of over €50bn is likely to be needed over the period up to 2050, most of it incurred over the next decade (Chart 6).3

This amounts to close to two percentage points of GNI* each year over the next decade.

And it will draw on resources similar to those that are needed to increase the supply of housing in Ireland.

Chart 6: Cumulative additional investment to achieve climate targets

Source: TIM model and calculations of authors of Conefrey et al (2024) ‘Fiscal Priorities in the Short and Medium Term’.

Chart 7: Global trade restrictions imposed since 2009

Source: Global Trade Alert. Notes: Data includes all measures introduced globally that restrict cross-border flows of goods, services and foreign direct investment. Last observation 2023.

Geo-economic fragmentation

Let me now turn to geo-economic fragmentation.

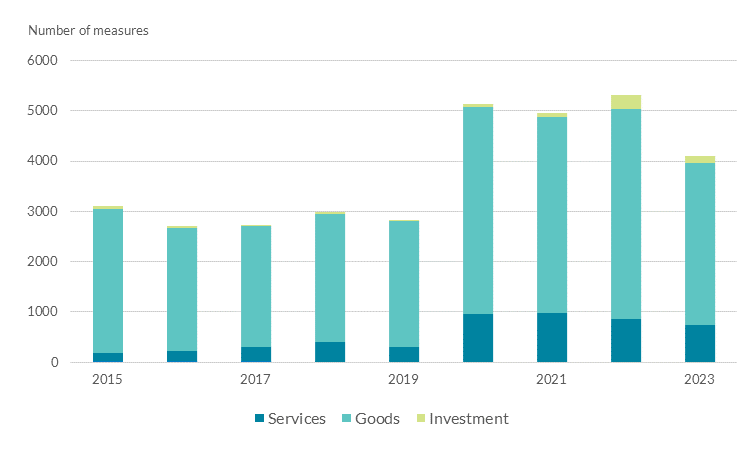

The global economy is becoming increasingly fragmented, in light of growing geopolitical tensions.

We see that in the rising number of trade restrictions that have been introduced at a global level in recent years (Chart 7).

We also see it in governments increasingly looking to reduce national exposure to geopolitically unaligned countries for the production of strategic goods.

This has led to the emergence of a whole new vocabulary around FDI, including “re-shoring”, “friend-shoring” or “near-shoring”.

And the impacts on FDI flows are already visible.4

Now, you may wonder what infrastructure has to do with this.

Ultimately, in a world that is fragmenting and FDI flows increasingly depend on geopolitical considerations, maintaining competitiveness will be crucial.

This is particularly relevant for Ireland, because our economic model has embraced – and is dependent on – globalisation.

So the risks of a more fragmented global economy are amplified for us.

Of course, Ireland already has a number of characteristics that make it competitive in terms of foreign investment.

It is part of the single market; English-speaking; has a competitive corporate tax regime; a common law system; and high levels of educational attainment.

But the one area where Ireland often lags other countries in cross-country measures of competitiveness is infrastructure.

Indeed, while Ireland ranked 4th out of 67 economies overall in the most recent ‘World Competitiveness Rankings’, it ranked 17th in terms of infrastructure.5

Within that, Ireland performed relatively poorly on management of water infrastructure, the density of road and rail networks, and energy infrastructure.

Capital investment in the infrastructure of the State will be important to ensure that Ireland maximises its chances of succeeding in a more fragmented world.

And it is not just about competitiveness.

Ireland is heavily reliant on imported natural gas to generate electricity.

As we saw during the energy crisis, this leaves us very vulnerable to geopolitical risks that affect the supply of energy.

The impact of higher gas prices following Russian’s war against Ukraine and its people was very serious for us.

This demonstrates the intertwined nature of these structural shifts.

Transforming our energy system is not just essential for the transition to net zero, but will also reduce our exposure to geopolitical risks.

Digitalisation

Let me now turn to digitalisation.

Many companies operating in Ireland are at the forefront of technological innovation globally.

But the world around us is changing very quickly, with the emergence of new technologies at a rapid pace.

Continued digitalisation, particularly the adoption of more advanced technologies, will be an important enabler of future growth in living standards.

But it can also be expected to place additional pressures on our infrastructure, especially in terms of energy.

Take advances in AI, for example.

While there is significant uncertainty around the impact of AI, it certainly has the potential to increase productivity and contribute to scientific advancement.

However, the development of GenAI models requires substantial computing power and data storage infrastructure.

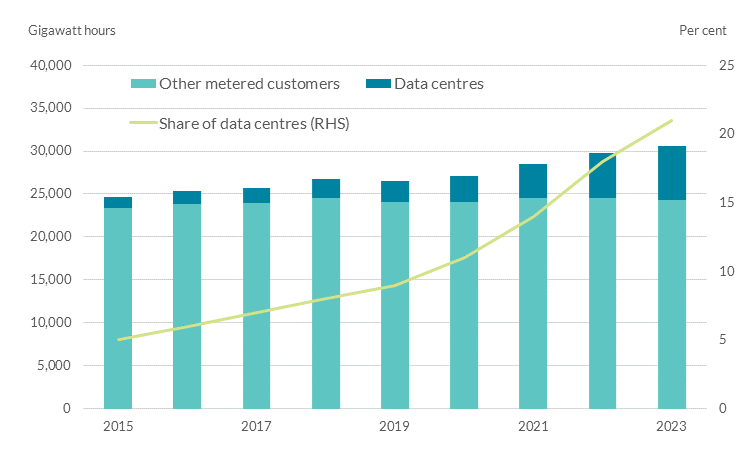

This requires energy, and we have already seen rapid growth in electricity consumption by data centres in recent years (Chart 8).

As data becomes a more important commodity in an increasingly digital global economy, we need to plan for the infrastructural implications of that transition.

Chart 8: Data centres have been accounting for a greater share of energy consumption

Source: CSO.

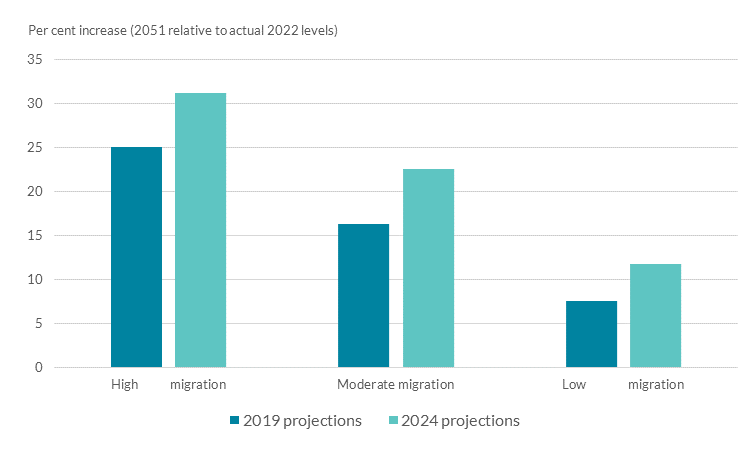

Chart 9: Ireland’s population is expected to rise faster than previously expected

Source: CSO.Notes: For the 2019 projections, using the F2 fertility assumptions. For the 2024 projections, there was only one fertility assumption used.

Demographics

Finally, let me turn to demographics.

Our population has recently grown faster than previously expected.

And, as we look ahead, the latest projections by the CSO have been revised upwards, with the moderate migration scenario pointing to a population of around 6.4mn by 2050 (Chart 9).

So we need to have the infrastructure that supports that larger population.

But it is not just the number of people in Ireland.

Advances in public health, medicine, and living conditions means people are living longer lives. Across the world, populations are ageing.

A favourable demographic composition has been a part of the success of the Irish economy over the last fifty years.

But this is fading and will ebb further as the population ages rapidly from the end of this decade.

This also has significant implications for our infrastructure, whether it is the type of housing we build or the capacity of our health service.

The macro-economic trade-offs of increased investment in infrastructure

Overall, it is clear that – in the years ahead – additional investment in infrastructure will be needed.

Delivering that additional investment, though, requires labour and other resources, which are constrained in the current environment.

This presents macro-economic trade-offs that need to be managed carefully.

Let me try and illustrate these trade-offs with an example.

I’ll focus specifically on housing, though – as I mentioned earlier – this is just one of several sources of additional investment that will be required in future years.

In an in-depth piece of analysis that we published two week ago, we updated our estimates of the underlying demand for housing, given demographic trends.

These suggest that around 52,000 new homes per year will be required out to the middle of this century to meet underlying demand.

This is an increase of around 20,000 homes relative to last year’s output.

One way of illustrating the trade-offs is by examining the macro-economic impact of that additional supply not coming to stream.

And then comparing that to the macro-economic impact of the economy adjusting to those higher levels of housing supply.

Let me start with the former.

In the absence of higher housing supply, and given growth in underlying demand, both house prices and rents would rise faster than would otherwise be the case.

The increase in the cost of housing services would feed into higher consumer prices, weighing on real household income and consumption.

The increase in prices also leads to an increase in wages and the cost of doing business in Ireland, and – so – the price of Irish exports relative to trading partners.

Our analysis suggests that total economic activity would be lower than what would otherwise be the case.

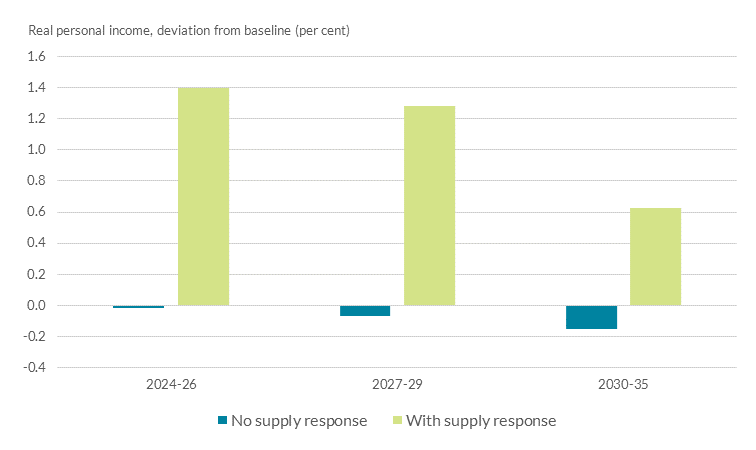

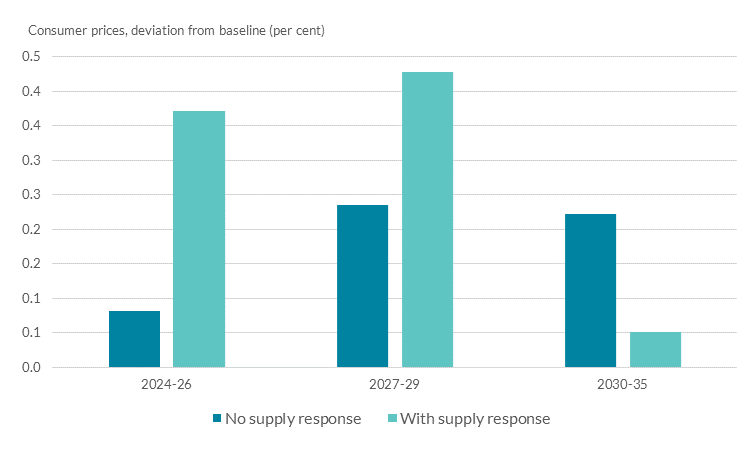

Now consider the case where housing supply does respond to provide an additional 20,000 units.

Increasing housing output to levels consistent with meeting long-run demand would provide a significant stimulus to domestic demand.

Within an already tight labour market, this would put upward pressure on both wages and prices.

Over time, however, higher housing supply, by boosting the capital stock of the economy, leads to a moderation in prices.

All models, of course, are a simplification of reality.

But this analysis illustrates the trade-offs associated with dealing with current infrastructure deficits, as well as future infrastructure needs.

Ultimately, especially in light of underlying increases in our population, additional infrastructure leads to higher living standards (Chart 10).

But, in the interim, such additional investment could contribute to demand-supply imbalances, especially given the current cyclical position of the economy (Chart 11).

This is the source of the trade-off we face, which ultimately matters for everyone.

Chart 10: In absence of additional investment, living standards are lower

Source: Central Bank of Ireland (2024), ‘Economic Policy Issues in the Irish Housing Market’.

Chart 11: But the interim period can lead to added supply-demand imbalances

Source: Central Bank of Ireland (2024), ‘Economic Policy Issues in the Irish Housing Market’.

Managing the macroeconomic trade-offs

Recognising and managing these macro-economic trade-offs is a key challenge for domestic economic policy.

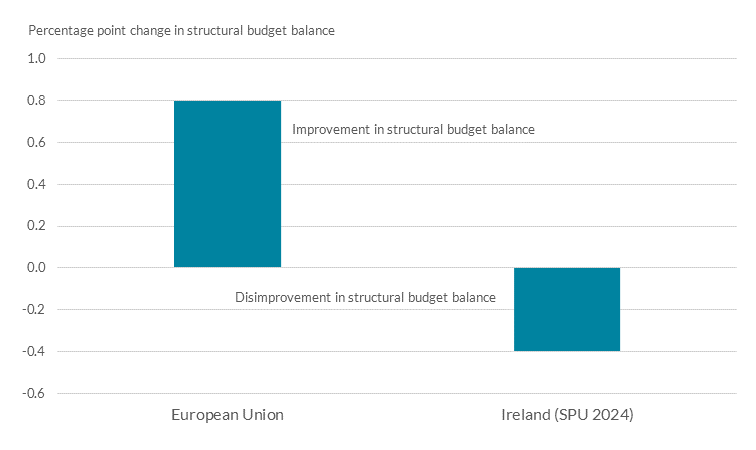

From a fiscal perspective, a key dimension of that is setting the overall fiscal stance appropriately.

At the current juncture, this means not adding excessive stimulus to an economy that is already operating at capacity.

And, within that overall fiscal envelope, seeking to prioritise investment.

Such an approach would enable the necessary increases in investment to be sustainable over time, reducing the risk of overheating or poor value for money.

Managing the macro-economic trade-offs also needs to consider the interaction between different macroeconomic policy levers.

The interaction between monetary policy – set for the euro area as a whole – and fiscal policy – set domestically – is particularly important in this respect.

With growing confidence that euro-area wide inflation will reach its 2% target in 2025, the ECB’s Governing Council has reduced interest rates by 50bps since June.

Put differently, the ECB’s Governing Council has reduced the degree of monetary policy restriction – and markets expect that to continue into next year.

In the context of both the current cyclical position of the Irish economy, as well as the evolving monetary policy stance at the euro area level, a prolonged period of expansionary fiscal policy risks generating persistently higher domestic inflation.

Fiscal plans outlined earlier this year already pointed to Ireland’s expansionary fiscal stance being in contrast to the contractionary stance at the level of the EU as a whole (Chart 12).

And this week’s budget announcement added further stimulus to a capacity-constrained economy.

This increases the risk that part of that extra stimulus will translate into higher prices, with implications for competitiveness as well as value for money.

Chart 12: Ireland’s fiscal position is expansionary, in contrast to the EU aggregate

Source: Ameco, Department of Finance SPU 2024 (for Ireland).Note: Chart shows the cumulative change in the structural budget balance in 2024 and 2025. Negative values indicate a disimprovement in the structural balance, positive values denote an improvement.

Another important dimension of managing the trade-offs is smoothing the pro-cyclical tendencies of infrastructure investment.

Or, put differently, seek to guard against the ‘stop-start’ dynamics in public investment that we have observed in the past.

Here, the establishment of the Infrastructure, Climate and Nature Fund is an important intervention that can help limit the pro-cyclicality of public investment.

The Fund will provide for resources for spending in a future downturn to support expenditure through the economic and fiscal cycle.

Managing the macro-economic trade-offs also extends beyond fiscal policy.

Our analysis suggests that delays in planning and delivery of public infrastructure can materially reduce the benefits of such expenditure. 7

This includes through a persistently lower level of private investment, which is either ‘crowded out’ or not enabled to happen.

Reducing planning frictions can ease some of the macro-economic trade-offs associated with higher public investment.

Similarly, our analysis suggests that measures to support productivity of construction can also play an important role in easing macro-economic trade-offs.8

Ireland’s construction sector has had investment levels below European peers for more than a decade.

And the structure of the sector – consisting of a large number of small businesses – means that construction cannot easily benefit from economies of scale.

Of course, some of these trends reflect the long shadow of the financial crisis.

But the outcome is that productivity in the sector is lower compared to other euro area countries.

Policy can therefore look to incentivise greater scale and productivity in the sector.

Such non-fiscal interventions can be particularly impactful in the context of the current cyclical position of the economy.

As the labour market remains relatively tight, interventions that support productivity can ease the pressure on resources that a number of infrastructure projects potentially are seeking to draw upon.

Conclusion

Sound investment today is critically important for laying the foundations for the future wellbeing of the population of Ireland.

It is clear that the next decade will require significant investments in our infrastructure.

Achieving that requires careful assessment and management of the macro-economic and budgetary trade-offs associated with such levels of investment.

Ultimately, that will enable the necessary increases in infrastructure investment to be sustainable over time.

Thank you for your attention.

[1] I am grateful to Patrick Haran, Thomas Conefrey, Robert Kelly and Martin O’Brien for their advice in preparing these remarks.

[2] See, for example, EirGrid and SONI (2024) ‘Ten-Year Generation Capacity Statement, 2023-2032’

[3] See Conefrey et al (2024), ‘Fiscal Priorities in the Short and Medium Term’, Central Bank of Ireland, Quarterly Bulletin, 2024 Q2.

[4] See, for example, IMF (2023) ‘Geoeconomic fragmentation and foreign direct investment’.

[5] See National Competitiveness and Productivity Council (2024), ‘IMD World Competitiveness Rankings’, Bulleting 24-4.

[6] See Central Bank of Ireland, Quarterly Bulletin, 2024 Q3.

[7] See Conefrey et al (2024), ‘Fiscal Priorities in the Short and Medium Term’, Central Bank of Ireland, Quarterly Bulletin, 2024 Q2.

[8] See Central Bank of Ireland, Quarterly Bulletin, 2024 Q3.