Enabling higher housing supply to bolster living standards, now and in the future - Remarks by Deputy Governor Vasileios Madouros to the Housing Infrastructure and Planning Convention

26 September 2024

Speech

Good morning everyone.1

Thank you very much for the invitation to take part in today’s conference.

The theme of the conference – around housing infrastructure – is particularly relevant to the current challenges facing the Irish economy.

Overall, the economy has been performing well, despite a number of external shocks in recent years, amid an increasingly uncertain global environment.

Domestic economic activity has continued to expand, employment is at record highs and household incomes have grown strongly.

In that context, a key challenge for public policy is ensuring that our infrastructure keeps up with the pace of expansion in the economy.

And, within infrastructure, one of the main priorities from a public policy perspective is housing.

So, in my remarks today, I will cover our economic assessment of the key factors that will shape the housing system’s ability to increase supply.

The scars of the financial crisis on the housing market

Before looking ahead, though, let me start by looking back.

Over the past two decades, the Irish housing market has undergone extraordinary volatility, having experienced one of the most amplified boom-bust cycles globally.

The financial crisis left persistent scars on the construction sector.

Many companies went out of business and many construction workers emigrated from Ireland following the crash.

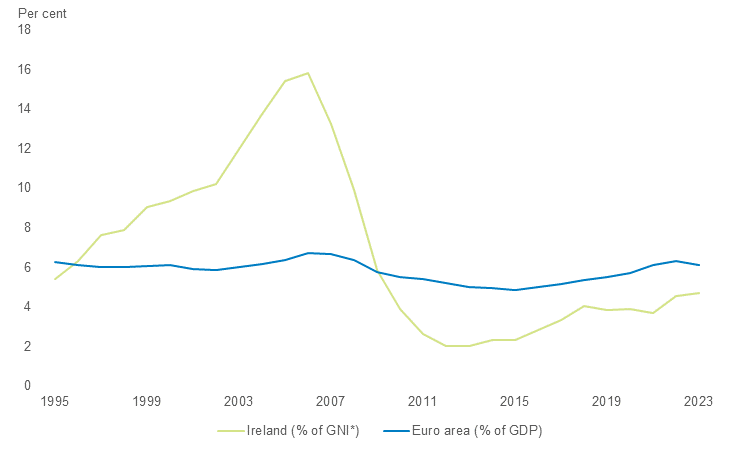

This boom-bust cycle has had long-lasting implications for housing supply, with housing output as a share of national income in Ireland being significantly below the euro area average for a prolonged period (Chart 1).

Amid a strong recovery of the broader economy, and faster than expected population growth, this has led to a persistent mismatch between underlying demand for, and supply of, housing.

Between 2011 and 2022, our population grew by 12.2%, whereas the housing stock grew by only 5.9%.

Chart 1: Housing investment as a share of national income has been below the euro-area average for a prolonged period

Source: CSO and Eurostat.

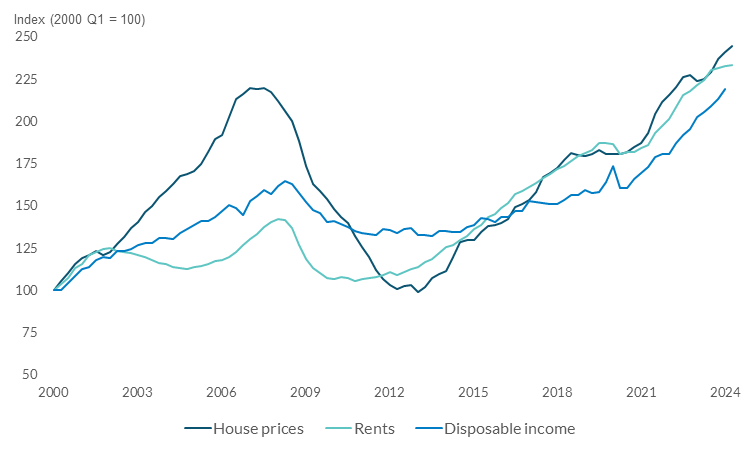

Chart 2: House prices and rents have both risen faster than household incomes over the past decade

Source: CSO and Central Bank of Ireland calculations.Notes: Last observation house prices & rents 2024Q2, disposable income per household 2024Q1.

This mismatch between demand and supply for housing has resulted in growing housing affordability challenges.

House prices and rents have risen faster than incomes over the past decade, stretching household budgets (Chart 2).

This has clear societal and distributional implications, as evidenced by the degree of public policy focus devoted to housing in recent years.

And it also has macroeconomic and aggregate implications.

For example, the availability of housing, at affordable prices and in locations close to economic activity, can affect employers’ ability to attract labour.

Indeed, when we go around the country talking to businesses, one of the recurring themes we hear relates to the challenges that they can face in attracting employees because of housing constraints.

This, in turn, is affecting their decisions on where and how to grow and invest.

So, in addition to the clear impact on individuals, the imbalance between housing demand and supply can constrain the economy’s ability to expand, with adverse implications for the sustainable growth in living standards.

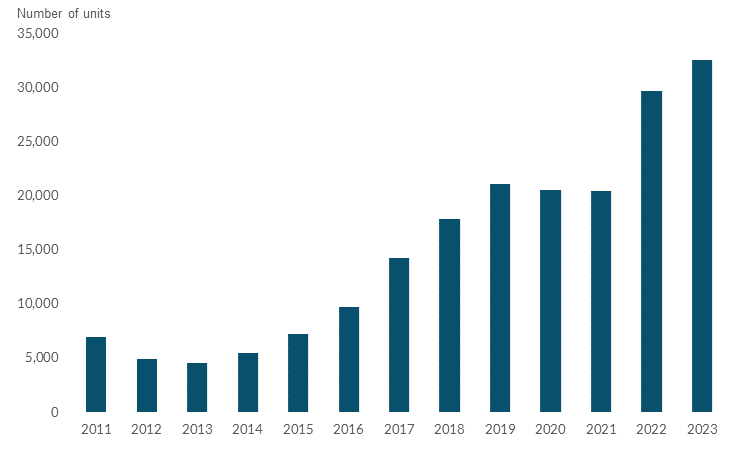

Of course, when looking at more recent developments, it is important to highlight the significant increase in housing output we have seen in recent years, and the policy action that has accompanied it.

In 2022 and 2023, housing completions increased rapidly, beyond the expectations of many, including previous Central Bank forecasts.

Completions rose from close to 20,000 a year between 2019-2021 to around 33,000 in 2023 (Chart 3), approaching previous estimates of the underlying annual demand for housing units.

Chart 3: There has been a significant increase in housing supply since 2019

Source: CSO.

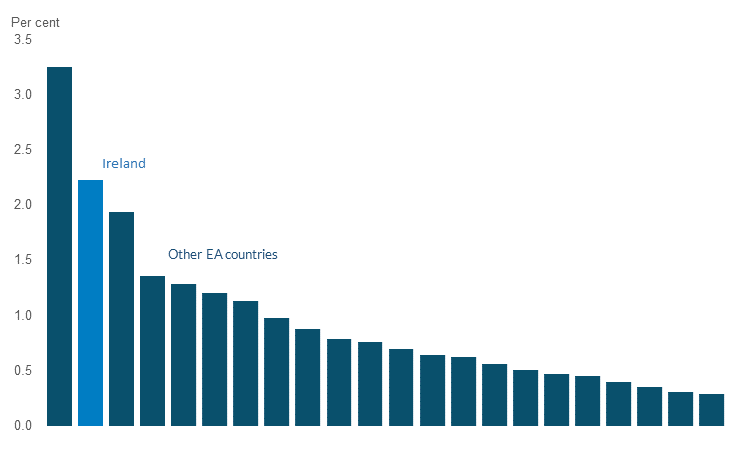

Chart 4: Irish government housing expenditure is high relative to the rest of the euro area

Source: Eurostat, CSO.

This has been despite the rapid increase in interest rates over the period, which typically weighs on residential investment.

The increase in housing supply has taken place in the context of a growing policy focus on housing delivery, across a range of dimensions.

From a fiscal perspective, for example, State spending on housing is now among the highest in Europe relative to the size of the economy (Chart 4).

And it is as high, proportionately, as it was in 2008, having increased from €1.2bn to €6.5bn since 2015.

Estimating future housing needs

Let me now look ahead.

In an in-depth piece of analysis that we published last week, we updated our estimates of the underlying demand for housing, given demographic trends.

And, by that, I don’t just mean demand for places to buy. I mean demand for places to live.

Our updated estimates take into account two factors.

First, updated population projections by the Central Statistics Office (CSO), which have been revised upwards, including in light of the latest Census.

Second, the degree of “pent-up” demand for housing that has accumulated over the past decade.

One way of illustrating that “pent-up” demand is through trends in household formation at younger age groups.

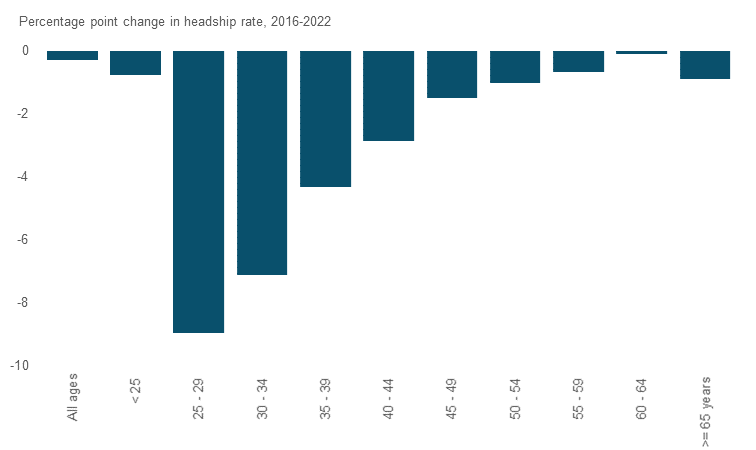

Since the 2011 Census, younger people have recorded the largest declines in household formation rates (‘headship’), reversing the previous upward trend evident up to then (Chart 5).

Chart 5: Younger people have seen a particularly sharp fall in the headship rate between 2011 and 2022

Source: CSO

This is consistent with younger people either living in their family home or living with others, as opposed to forming an independent household, for longer than previously.

It is an illustration of how “pent up” demand manifests in practice.

So, taking into account both future population growth and the gradual unwinding of pent-up demand, our updated estimate is that around 52,000 new homes per year are required out to the middle of this century.

This is an increase of around 20,000 homes relative to last year’s output.

Of course, and I do want to emphasise that, there is uncertainty around these estimates.

They rely on assumptions, for example on future population growth or average household size, which are uncertain.

It is important that these assumptions are revisited periodically, in light of incoming data, especially to the extent that estimates such as these are then translated into targets for public policy.

But, the main message still holds: there is a need to further scale up housing supply in the years ahead.

The heart of the challenge: viability of construction at scale

How can Ireland’s housing system transition towards such a level of supply?

There is no doubt that this is a challenge for public policy, with no easy or quick fix.

One key theme underpins our assessment: at its core, the underlying challenge relates to the housing system’s ability to produce viable housing projects at the required scale.

Put differently, there is a disconnect between the cost of producing housing units by the construction sector at scale and the (sale or rental) prices that are within the reach of Irish households, given income levels.

From our analysis, we have identified three broad policy areas that can bolster viability at greater scale.

Firstly, the availability of zoned and serviced land. This is the starting point for construction and it entails a key role for the State.

Capital spending can ensure that the supporting infrastructure – water, sewerage, energy and transport – is provided on time, at scale, and in locations closest to housing demand.

Secondly, the planning process and the system of housing and building regulation.

The role of delays, objections, and bottlenecks in the planning system is hard to quantify or to compare internationally.

But, the evidence suggests that a more efficient system could both unlock additional supply and reduce construction costs.

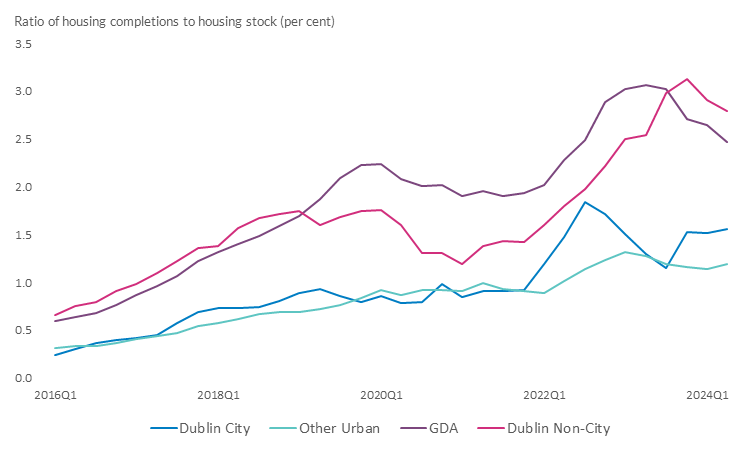

Our analysis also points to a strong pattern of increased supply in the regions surrounding Dublin, but with weaker supply nearer to the city centre and other urban centres such as Cork and Galway (Chart 6).

Chart 6: The increase in supply has been higher in commuter belts than in urban centres

Source: CSO and Central Bank calculations.

Note: Annual completions by region divided by 2022 Census estimates of households in permanent dwellings (a proxy for the housing stock). Regions defined as follows: Dublin City given as Dublin City Council area separately. Dublin Non-City (Fingal, DLR, South County); GDA (Meath, Kildare, Wicklow); Other Urban (Galway, Cork, Limerick, Waterford).

From an environmental, as well as an infrastructure, perspective, it is important that policy tackles any frictions that may be slowing down the development of housing nearer to employment centres, including higher-density housing.

Thirdly, productivity and capacity of the construction sector.

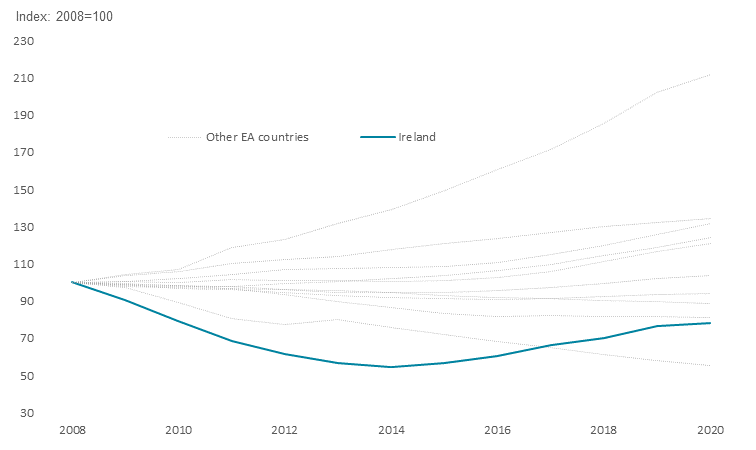

Our analysis suggests that Ireland’s construction sector has had investment levels below European peers for more than a decade (Chart 7).

And the structure of the sector – consisting of a large number of small businesses – means that construction cannot easily benefit from economies of scale.

Of course some of these trends reflect the long shadow of the crisis.

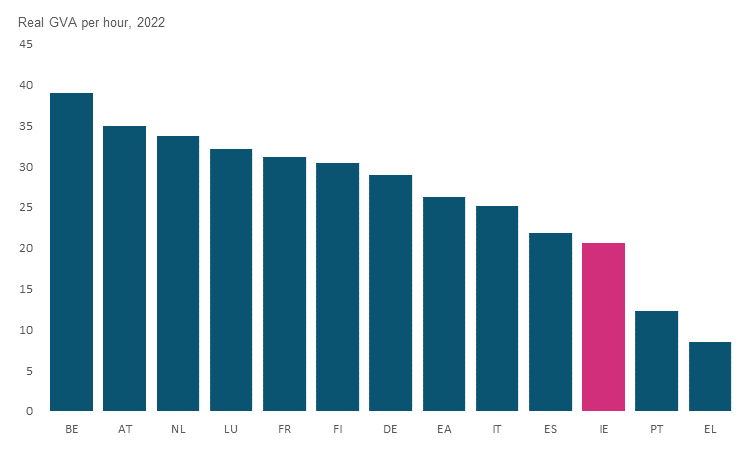

But the outcome is that value-added per hour worked in the sector is lower compared to other euro area countries (Chart 8).

Policy can therefore look to incentivise greater scale and productivity in the sector, including through enhanced adoption of modern construction methods or standardisation of designs.

This is particularly relevant given that the broader economy is at full employment, and meaningful addition of new workers may prove a challenge.

Policy measures in these three areas would reinforce each other and, collectively, help to support greater viability at scale.

Chart 7: The capital stock of the construction sector is further below pre-crisis levels than peers

Source: Eurostat.

Chart 8: Construction sector productivity is below comparator euro area countries

Source: Eurostat and Central Bank calculations.

Assessing the financing of needs for future housing supply

Let me now turn to the question of financing of higher levels of housing development.

Financing, of course, is a necessary ingredient for construction activity.

But, it is also important to put its role into context.

Additional financing alone cannot rectify housing imbalances, in the absence of measures to address the structural factors that I mentioned above.

Indeed, as I’ll set out, our own analysis suggests that finance availability is not the main factor constraining housing supply.

With that context, let me zoom in on the question of financing.

The first key theme I want to highlight is the importance of diversity.

The nature of financing in recent years has been very different compared to the pre-2007 housing boom.

Back then, much of the financing took the form of debt funding provided by the domestic banking sector.

By contrast, financing flows underpinning development in recent years have exhibited a healthy diversity.

Indeed, it is surprisingly difficult to estimate with precision the quantum and sources of financing of housing development underpinning the units supplied in 2023.

In part, that is because some of this financing is stemming from sources not regulated by the Central Bank.

So this is an area where we want to continue to enhance our understanding in the years ahead.

While there is uncertainty, we estimate that around €10bn-€11bn of development financing likely underpinned the housing supplied in 2023.

The State, the domestic banking sector, and non-bank financial intermediaries, all played important roles.

This diversification, with a key role played by inflows of debt and equity from overseas, is a strength from a macro-financial perspective.

It enables risk sharing and can reduce the sensitivity of financing to the domestic economic cycle.

So it will be essential to maintain that diversity to support a sustainable transition towards higher levels of supply.

Looking ahead, we estimate that, over and above the continuation of financing underpinning last year’s delivery, an additional €6.5bn-€7bn would be required for an additional 20,000 units.

While the State has an important role to play, most of the additional financing will need to stem from private – domestic and international – sources.

The State has already increased capital spending on housing substantially.

Its role will remain important, especially in meeting the needs of those at the lower end of the income distribution.

But, given the diversity of housing needs across the population, most additional delivery will stem from a privately financed and developed market.

Is there capacity to provide these additional financial flows?

Assuming that the State maintains the same proportion in financing as in 2023 delivery, we estimate additional private sector capacity would need to be in the region of €5bn.

The precise split between debt and equity depends on assumptions, such as the average loan-to-cost associated with development finance.

But a reasonable split would be an additional €3bn in debt financing and €2bn in equity financing.

Recent announcements from the domestic banks suggest up to €1.25bn of additional loan financing commitments are already in train.

In addition, we estimate that undrawn, and already committed, debt funding within risk appetite at bank and non-bank lenders, is around €1bn-€2bn.

Beyond this, certain cross-border debt financing flows, particularly important for larger-scale developments, are another potential financing source not captured in our data.

Together, these sources can make a substantial contribution towards increased debt financing.

Our assessment overall is that, within sustainable underwriting parameters, there is scope for the financial system to make a substantial contribution towards higher levels of housing output.

The issue of equity financing presents more of a challenge.

We estimate that up to €2bn of additional equity finance, above and beyond that committed to underpin 2023 supply, will be required every year to deliver an additional 20,000 homes.

Equity can come from developers’ own balance sheets, or from external sources, which could be domestic in nature, or more likely will require foreign inflows from specialist funds and other institutional investors.

Our engagement with sectoral experts suggests that, for a range of reasons, access to sufficient equity finance remains a difficulty, particularly for smaller construction and development businesses.

This does take me back to the three fundamental areas of policy focus outlined above, because progress in these areas can support viability and, in turn, facilitate access to financing flows.

For example, greater availability of zoned and serviced land as well as more certain and speedier planning decisions would help unlock additional equity financing, including from abroad.

Indeed, from an international perspective, the Dublin market continues to offer competitive yields with respect to other European locations.

Similarly, a more productive construction sector, operating at greater scale, would be in better position to build or access equity finance, which would in turn also facilitate access to debt finance.

Still, certain policy measures may also support financial flows.

These could relate, for example, to initiatives that ‘crowd-in’ additional equity through State participation.

An example here is ISIF’s model of using its capital to act as a catalyst for attracting third-party co-investment.

Importance of resilience in finance

Let me now turn to the importance of the resilience in finance, a dimension that is particularly close to our own mandate at the Central Bank.

If there is one lesson from the past 20 years, it is that additional housing supply cannot – and should not – be based on shaky financing foundations.

The costs of that, for society as a whole, are too large.

We can see that from the persistent scars that the crisis left on the construction sector, and the associated societal and economic implications of this period of undersupply.

Equally, though, it is important to recognise that measures to safeguard resilience in finance entail both benefits and costs.

And, on that, let me be clear. Our approach, at the Central Bank, is not to aim for resilience at any cost. That would not serve society well.

Our aim is to balance the benefits and costs of our policy interventions carefully.

Let me explain this with reference to the different macro-prudential measures that we have introduced over the past decade to safeguard resilience of finance.

These are not aimed specifically at development finance, but they do interact with the housing market in different ways.

Most directly, of course, the mortgage measures aim to ensure sustainable lending standards in the mortgage market.

These measures have placed limits on the share of new lending at higher levels of household indebtedness since 2015.

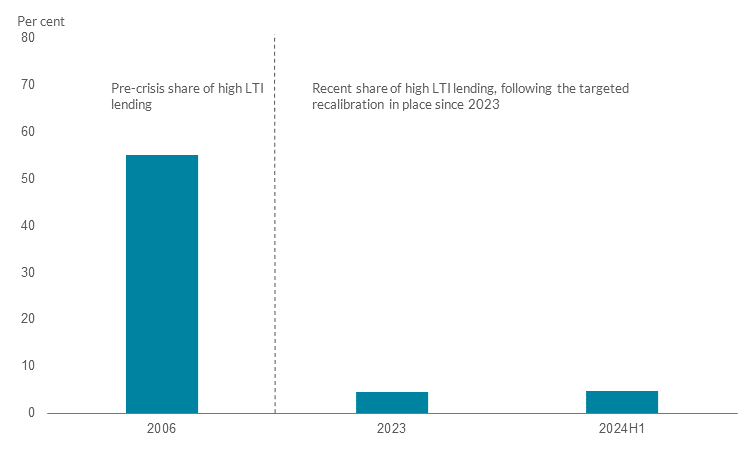

In 2022, we concluded an in-depth review of our framework. As part of that, we made a targeted adjustment to the calibration of the measures, which took effect at the start of last year.

Our refreshed calibration was an outcome of our assessment of the evolving balance between the benefits and costs of the measures.

Our judgement was that, due to the ongoing imbalance between supply and demand in the housing market, the costs of the measures at our previous calibration had grown over time, even if their benefits remained substantial.

Our move from an LTI of 3.5 to 4 for First Time Buyers was an acknowledgement of the need to ease the costs of the measures, while safeguarding their resilience benefits for the mortgage and housing system.

Indeed, lending at very high levels of indebtedness continues to remain well below the peaks that we saw in the mid-2000s (Chart 9), even following our refreshed recalibration.

Chart 9: The share of new lending at high levels of indebtedness is much lower than in the mid-2000s

Source: Central Bank of Ireland.

Note: High indebtedness relates to lending at loan-to-income multiples greater than 4. FTB and SSB lending for property purchase or self-build purposes. Excludes equity release, top-up and refinance mortgages.

In terms of bank resilience, our macroprudential and microprudential frameworks aim to ensure that the banking system is better able to absorb – rather than amplify – adverse shocks.

This, in turn, enables an sustainable flow of financing to support economic activity.

Again, the calibration of the macroprudential capital buffers for banks, also reviewed in-depth in 2022, aims to balance the macroeconomic benefits of greater resilience, against the macroeconomic costs of higher capital levels through the impact on lending.

More recently, we introduced measures for property funds authorised in Ireland.

In part, this recognises the evolving nature of financing of the domestic property market, with a greater role for non-bank finance.

While the vast majority of property funds invest in commercial buildings – for example, offices, retail or logistics – there has also been growth in residential assets by these funds.

Our measures aim to safeguard the resilience of this growing form of financial intermediation, by guarding against leverage-related vulnerabilities.

Again, in calibrating these measures, we were careful to balance their benefits and costs.

Indeed, the feedback we received from our consultation process was an important input in strengthening our understanding of that balance.

In response to that feedback, we incorporated a longer implementation period for the measures; we excluded social housing funds, given their characteristics; and we made a methodological adjustment for funds pursuing development activity.

We are now monitoring closely the implementation of these measures and are focused on assessing their impact.

It is positive that, over the course of 2023, we continued seeing net flows into property funds, including those invested in residential property, and we have also seen continued demand to launch new funds over the course of 2023 and 2024.

Although inflows were lower than in 2022, consistent with global trends given the rise in interest rates, this points to continued willingness of investors to provide capital.

Conclusion

Housing is a multi-faceted policy challenge, comprising a blend of public and private activity.

Ultimately, the capacity of the housing system to meet underlying demographic needs is a key driver of sustainable growth in living standards, now and in the future.

Our assessment is that policy focus should be in the areas of supply-side reform.

These include enabling infrastructure, regulation and planning processes, and measures to support productivity and capacity in the construction sector.

Of course, transitioning to the delivery of an additional 20,000 housing units a year also has broader macroeconomic implications, which need to be managed carefully.

This is especially the case in the current context of the economy operating at capacity, and amid broader needs for infrastructure investment.

Measures that support the productivity of the construction sector can ease some of the macro-economic trade-offs.

However, these trade-offs also underscore why any additional capital spending to support housing supply needs to be prioritised within the overall envelope of the Governments’ net spending rule.

Thank you for your attention.

[1] These remarks build heavily on an

Article (PDF 3.03MB) published in the Central Bank’s

Quarterly Bulletin 3, 2024. I am particularly grateful to Thomas Conefrey, Fergal McCann and Martin O’Brien for leading that work. And to Patrick Haran for his help with these remarks.