Building Economic Resilience - Governor Gabriel Makhlouf at the IIEA

20 February 2025

Speech

Good afternoon. It's nice to be back at the IIEA.

The beginning of every year is a time to think about the future, reflect on the lessons learned – at least those that we can still remember – from the past, and plan and prioritise what we will do in the year ahead.

Today I want to talk about some of the areas the Central Bank will be working on in 2025, but also some of the issues that I believe are priorities for economic policy in general. The theme of my remarks will be the importance of building economic resilience in the face of the economic transitions that we are living through and that are ahead of us.

We find ourselves emerging from a period where, out of necessity, households, businesses and policymakers, have had to deal with the immediate – and in some instances unprecedented – short-run challenges created by a variety of global economic and geopolitical crises.

From pandemic to war and from supply chain disruption to inflation, we find ourselves today facing into a period of both challenge and opportunity for the Irish economy, against an uncertain international backdrop.

Indeed, as we look to the future, it is clear that we are navigating a new era of change to the international order that has underpinned global cooperation since World War II.

The global geopolitical landscape faces significant strain and complexity, driven by competing interests, shifting alliances with different values and increasingly independent economic blocs.

Policy-induced geoeconomic fragmentation has moved from being a risk to becoming a reality, affecting trade and foreign direct investment flows. As a small, open economy, Ireland finds itself at the crossroads of these geopolitical headwinds, deeply exposed to the challenges and complexities and at risk, to paraphrase Václav Havel, of being thrown “repeatedly into the tumult of the world”.1

The financial system is changing too, driven by economic trends and, in particular, advances in technology. Being part of the broader economy, it has also been buffeted by the same shocks and, with some notable exceptions, has demonstrated its resilience. We want that resilience to be maintained, and strengthened where necessary.

With this in mind, I want to offer my perspectives on the outlook, and the associated implications for Ireland's economic policy and what it means for the Central Bank.

Throughout my remarks today, I will underline the ongoing need to build economic resilience through the transitions that Ireland is undergoing. Our objective should be that we do not just weather the current storm but we emerge stronger, more resilient and better prepared to face the challenges and, indeed, take the opportunities that are in front of us.

The economic outlook

Let me start by reflecting briefly on the current outlook which is, in summary, relatively favourable. Based on our most recent published forecasts from mid-December, we expect the domestic economy to grow in-line with its medium-term potential out to 2027, having been operating above that level in 2023 and 2024. One notable indication of the recent relative health of the economy is that the unemployment rate has stayed below 5 per cent for 36 consecutive months (3 years) since February 2022. This is the longest sustained period of low unemployment in the available monthly data back to 1983.

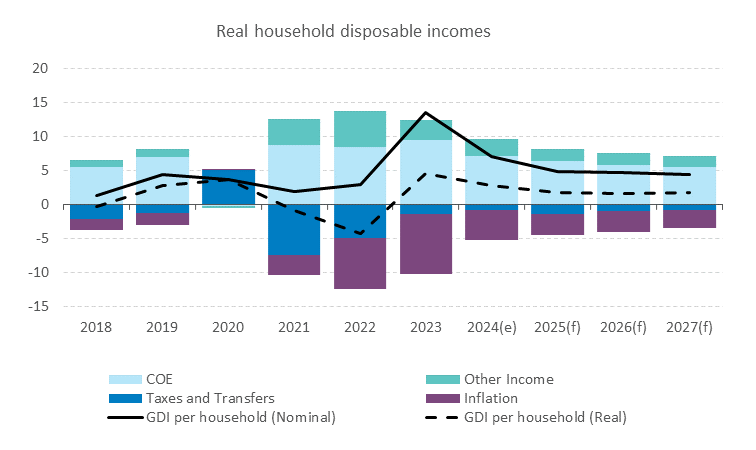

Unemployment is projected to remain low and headline inflation is being contained, while real household disposable incomes continue to rise. Chart 1

Chart 1: Real household disposable incomes

Source: CSO & Central Bank QB24 ForecastHowever, downside risks to this outlook have increased and there is a higher level of uncertainty, particularly as to how geoeconomic fragmentation will develop and the extent to which it will affect Ireland. In fact it feels as if we are in a period of fundamental or Knightian uncertainty, a period when some economists might be tempted to change career as they no longer see a future in economic forecasting. It feels a very very long time since our update in mid-December. Even before the concrete effects of more fragmented trade and economic relations materialise, heightened uncertainty will itself weigh on economic activity.

As an open economy with an export-led growth model, the Irish economy is more exposed than others to negative external shocks arising from changes to global trading patterns. More pronounced fragmentation would undo some of the gains from the greater interconnectedness that has stimulated growth in the economy over the last 50 years.

If we consider the important role that international investment and multinational enterprises play in the domestic economic model, we see how they drive a significant share of growth, tax revenue and employment in this country. It seems obvious that any reversal of this would be reflected in lower foreign direct investment, exports and productivity, all of which would serve to reduce overall economic growth with negative effects on the labour market and the public finances. Fragmentation could also result in higher and more volatile inflation, particularly for a country like Ireland that is highly dependent on imports.

Inflation

On inflation, at our last meeting three weeks ago, my colleagues and I (on the ECB’s Governing Council) decided to lower our three policy rates by 25 basis points. Last year we reduced rates by 100 basis points as inflationary pressures continued to ease and it became clearer that there would be a gradual convergence of inflation to our 2 per cent target during 2025.

Needless to say, the disinflation process remains subject to risks, and there is a very high degree of uncertainty surrounding the outlook. We stand ready to react to changes in the outlook, for both inflation and growth, which is why my colleagues and I continue to believe that we should not commit to any specific future path for interest rates.

Headline inflation in Ireland (measured by the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP)) has moderated, and is currently below 2 per cent. Stronger than expected economic growth in recent years, over and above the economy's potential rate, has brought into sharp focus domestic supply and infrastructure constraints (which I will discuss shortly).

These, in turn present a situation where globally-determined inflation in Ireland is declining substantially, but more domestically-driven inflation remains significant. In particular, services inflation remains high at just below 4 per cent, and is expected to be the main positive contributor to headline and core inflation out to 2026. This reflects more significant domestic price pressures, driven in part by strong domestic demand and highlights the continued risk of overheating in the domestic economy.

Challenges and opportunities

As we look forward to the second half of this decade, and beyond, Ireland faces some profound economic challenges, as well as significant opportunities. Policy choices should aim to balance short-term priorities with longer-term policy objectives that will determine our living standards throughout the 2030s and beyond.

I see two particular economic challenges that need to be addressed without delay: the infrastructure deficits which are affecting housing, transport, energy, water and waste water, and the risks to the Exchequer from the over-reliance on a relatively narrow tax base, especially in the context of a changing global environment.

With the economy still operating somewhat above its potential currently, the infrastructure constraints that further limit sustainable growth in living standards have become apparent. The ability to deliver infrastructure is particularly important not least to maintain incentives for inward investment. It is even more important at a time of geoeconomic fragmentation.

High costs and delays in the delivery of infrastructure manifest themselves in lower value for money for the initial investment, as well as in asset price and rent inflation. In turn, these price rises can eventually feed through to higher wage demands and a higher cost of living and doing business more generally, thus damaging competitiveness. Persistent infrastructure deficits in key areas can also lead to consumption and investment opportunities being foregone or delayed, as the economy cannot supply the volume of goods and services society demands.

As for the risks to the Exchequer, Corporation Tax now accounts for 25 per cent of tax revenue. Over 90 per cent of it is paid by foreign-owned firms, with only a third (c.€5bn) of the proportion deemed ‘excess’ from domestic economic activity being put aside for the future. Corporation Tax is particularly vulnerable to geoeconomic fragmentation, whether as a result of trade tensions or changes in third-country policies. A substantial loss of the tax would push the budget into a deficit position, something that would have negative consequences for all of the required infrastructure development currently in the pipeline.

The challenges of infrastructure delivery and Exchequer receipts coincide with those that arise from a more structural and long-term perspective.

First, as outlined in recent research by the Central Bank, the potential growth rate of the Irish economy is set to halve to around 1.4 per cent by the middle of the century, as our working-age population declines. However, this analysis shows that an enhanced level of investment in physical and human capital to support productivity growth, and enabling people to stay longer in the workforce, can in part offset this decline.

This points to the opportunities available for economic policy to take action now, supporting continued sustainable growth in Irish living standards over the longer-run.

Ireland's ageing demographics pose significant challenges to our future labour supply and productivity, and to the sustainability of our long-term growth. As the conventional working age segments of our population shrink, the resulting pressure on government finances will intensify. The number of people of working age for each retiree in Ireland is set to halve from around four currently to two by 2050. This will create new demands for additional public expenditure relative to the present position.

This trend is not, of course, unique to Ireland. Across the EU, populations are nearing their peak and are projected to decline, with implications for the Union’s economic growth and geopolitical influence. The IMF predicts that total hours worked in Europe will decline over the next five years. These shifts carry far-reaching policy implications, impacting working age and pension sustainability, healthcare resourcing, infrastructure, and our broader fiscal resilience. Addressing these challenges requires forward-thinking strategies.

A positive development in Ireland in recent years has been the increase in labour force participation rates for older workers, enabled in part by improvements in life expectancy. I expect to see such participation increase over time as we re-assess how we think about ‘retirement’ and human capital appreciation over the life cycle.2

Estimates from the Department of Finance show that total age-related public spending is projected to rise by 6 percentage points of GNI* by 2050 (which would be the largest increase in age-related expenditure over this period across the EU). Moreover, in addition to meeting these new demands, the cost of maintaining existing levels of public services in future years will absorb substantial resources.

One of the more significant areas where concerted investment efforts are needed is the decarbonisation of the economy if Ireland is to meet the target of a 51 per cent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions relative to 2018 by 2030.

We still have an opportunity to make a considerable impact on reaching our targets, and the next five years will be critical for the transition towards climate neutrality, but there is considerable work to do. It should not need pointing out but 2030 is not far away; in fact it’s as far away as the start of the pandemic is behind us.

With current projections (from the Environmental Protection Agency) signalling a significant undershoot in meeting this target, estimates point to an additional annual investment need of around 1.7 per cent of GNI* to 2030, or €54.5bn in total by 2050 to achieve it, at least 20 per cent of which would likely comprise public investment. Over the period to 2030, this would constitute an increase of 8 per cent in public capital expenditure over and above what is currently envisaged in Budget 2025. And of course the costs of inaction are even bigger in the long term.

But our economy is in a good position to address these challenges. The near-term outlook speaks for itself and I welcome the Government’s commitment to the two long-term Funds which have now been established. The Infrastructure, Climate and Nature Fund and the Future Ireland Fund are important developments and will help to allay the emerging cost of the ageing and climate transitions, as will the auto-enrolment retirement savings scheme which starts this September.

The Commission on Tax and Welfare’s report provides a menu of options for broadening the tax base (and so future-proof the public finances). In the short-run this could help ease inflationary pressures while public capital spending is being increased, while at the same time helping to create a more sustainable tax revenue base and more resilient public finances with which future fiscal challenges can be addressed.

Importantly, the overall fiscal position should be designed to enable the significant investment needed to address the infrastructure deficits that are essential to removing the constraints to more sustainable growth in living standards, while guarding against the risks of overheating.

Implications for economic policy

Given the domestic and international backdrop, Irish economic policy has the opportunity over the next five years to make a substantial contribution to maintaining sustainable growth in living standards across our community for the decades ahead, notwithstanding the major geopolitical and global challenges.

First, policy choices should strive to reconcile short-term priorities with long-term objectives. Although short-term problems have a tendency to dominate policy debate, in devising solutions to these it is important to maintain a focus on long-term priorities.

In order to do so, I believe the following areas of policy focus should be considered:

- Prioritising capital expenditure and tax base broadening to create the economic and fiscal space for the necessary increase in investment needed in the coming years;

- Enhancing and introducing structural reforms to reduce the costs of infrastructure delivery and boost productivity in the construction sector;

- Further enabling increased labour force participation and productivity by supporting life-long learning and adaptation to technological change;

- Continuing to support efforts to mitigate geoeconomic fragmentation while protecting supply chain security. At EU level, this should include supporting actions to remove frictions in product and labour markets and harmonise rules and regulations across countries to improve the functioning of the Single Market, particularly for intra-EU trade in services. Related to this, it is important to ensure that competition policy frameworks are equipped to deal with the fast-changing environment in which we live in order to maintain the balance between innovation incentives and competition, particularly as AI changes the business and technological landscape.

Achieving decisive progress across these policy priorities would boost productivity which is at the heart of building resilience.

All aspects of policy – fiscal, structural, industrial, financial sector and monetary – have a role to play. With euro area monetary policy becoming less restrictive and the Irish economy expected to grow in-line with its medium-term potential, the role of domestic policy in maintaining macroeconomic stability comes to the fore. I have emphasised to the Minister for Finance the importance of the Government committing to rigorous expenditure control alongside an appropriate anchor or fiscal rule for budgetary policy to ensure the overall fiscal stance is appropriate, guards against pro-cyclicality and boom-bust dynamics and safeguards long-run fiscal sustainability.

This should support the creation of the necessary economic and fiscal space for the investment in infrastructure and the other structural reforms – in particular with regard to planning regulations – essential to Ireland's resilience and future prosperity.

The financial sector

As for the financial sector itself, it is core to much of what I have spoken about, from the transition to net zero, to financing infrastructure, to supporting investment and innovation and assisting in managing the implications of our ageing population. Financial sector policy needs to deliver appropriate levels of resilience to ensure the system is able to support households and businesses in good times, and in bad. We have seen the consequences of long-term and persistent costs of insufficient resilience for the broader economy. The financial sector has an important role to play in supporting the broader economy through the economic transitions we are living through.

I should add that this isn't just an issue for Ireland's financial sector. From a broader perspective, sustainably mobilising private savings across the EU for investment in Europe’s productive capital stock would also enhance the resilience of households, businesses and the economy as a whole. In this respect both domestic and EU policy efforts should be enhanced to translate savings into investment and create a more vibrant funding environment for infrastructure and innovation. The Savings and Investments Union must deliver if Europe is to regain its competitive edge, and if we are to find ways to unlock the €11.5 trillion held by Europeans in deposits and cash and channel it to drive European innovation, while maintaining our resilience in the face of future potential shocks.

The Central Bank of Ireland will continue to focus on its mission of maintaining monetary and financial stability while ensuring that the financial system operates in the best interests of consumers and the wider economy. In particular this year, we will work with peers and other stakeholders on the simplification agenda and look to enable properly-functioning markets that support innovation and productivity without undermining core policy objectives such as financial stability and investor and consumer protection.

In any drive to simplify, we need to be clear that we do not compromise on delivering the stability, resilience and protections that consumers and the wider economy need and that the public expects.

Conclusion

Let me conclude by going back to the beginning. Economic resilience is the ability of an economy to manage change, whether it is to withstand (or recover from) shocks or the more gradual evolution to a different state. There is no one-off solution to the challenge of building resilience.

It is a continuous process involving individuals, households, businesses and policymakers adapting to – and shaping – the context in which they live and operate. At a minimum, we have to focus on the fundamentals such as stable and sustainable macroeconomic frameworks, sound monetary policy that delivers stable and predictable prices, well-regulated financial systems and well-functioning markets.

Needless to say, we also need to focus on the medium term while managing the short-term and in particular what is in our control. We can do that best by having a clear understanding of our starting point, learning from the past to help plan the future, extracting signal from noise, distinguishing action from assertion, avoiding disinformation bubbles and, as Keynes, might have put it, not “losing ourselves in mere hypothesis but returning in some degree to first principles and, whenever we can, to such [facts] as there are”.3

What is undoubtedly not a hypothesis is that Ireland and our partners in Europe are undergoing significant economic transitions in climate, in demography and in technology. On the face of it, we are also undergoing a significant economic transition in how international trading relationships are made and nurtured. The growing fragmentation of the global economy is a challenge to Ireland's openness, which has been one of the defining features of its economy and a key platform for the country’s living standards. Building economic resilience – through investment in physical and human capital in particular – is the most effective way of helping to manage these transitions.