Governor’s Blog – The resilience of household borrowers

08 February 2024

Blog

At its latest meeting two weeks ago, the ECB’s Governing Council decided to leave its main policy rates unchanged. The rate of inflation is falling and any change in our monetary policy stance will depend on the data and evidence as we aim to reach our 2 per cent target in a sustainable way. I would like to use this blog to look at the impact of inflation and interest rates on mortgage borrowers, and whether we are seeing signs of increased financial distress amongst Irish households.

Overall the impact of inflation and rising interest rates on household borrowers in Ireland has been cushioned by nominal income growth, fiscal measures, and the relatively slow pass-through of monetary policy by lenders to household borrowing rates. The resilience of Irish households during this shock has also been supported by more than a decade of balance sheet repair after the previous crisis, and prudent new lending under our mortgage measures.

Although pockets of vulnerability exist, including among lower income borrowers and those with past repayment difficulties, in our analysis we have so far seen only small increases in early arrears at an aggregate level, which have been offset somewhat by falls in longer-term arrears cases. We are also seeing that the impact of high inflation has been mitigated by fiscal measures, including income tax breaks and energy price subsidies. In addition to the analysis we undertake, we are also informed by our engagements with industry bodies as well as through our civil society roundtables.

Effect of the interest rate shock

As inflation in Europe rose sharply in early 2022, market funding costs increased in late spring and the ECB began raising policy interest rates in July 2022. As I said, last month my colleagues and I decided for the third consecutive meeting to keep rates unchanged. When interest rates rose, the impact on borrowers varied by lender and loan product types. Rates on tracker mortgages increased in tandem with ECB policy rates. Non-banks began raising borrower interest rates in late spring 2022, while domestic retail banks only began increasing their standard variable rate (SVR) and new fixed rates in early 2023.

For example, the median interest rate on the stock of bank principal dwelling home (PDH) mortgage loan increased from 2.6 per cent in March 2022 to 3.6 per cent in September 2023, substantially lower than the change in ECB policy rates over this period. This reflects a large fixed rate share of existing mortgages (63 per cent) and the incomplete pass-through of monetary policy decisions to SVR and new fixed rate contracts.

Lending non-bank interest rates have seen more modest increases, again reflecting a large fixed rate share of loans as well as a decline in new lending by these entities beginning in mid-2022. Non-lending non-bank borrowers have generally seen the largest increase in interest rates, which is partly explained by the relatively high share of tracker and SVR loans in the portfolios of these entities.(1)

Reflecting the nature of fixed-term contracts in Ireland, a steady flow of borrowers are scheduled to roll off fixed rates over the coming years, which you can see in Chart 1. As of June 2023, 19 per cent of bank PDH mortgages were fixed with 0-2 years remaining until expiration and 44 per cent had greater than 2 years remaining. 22 per cent of loans were on tracker rates, with the remaining 14 per cent on an SVR. In the twelve months from June of last year, we expect that about one in ten PDH mortgages in Ireland will have seen their fixed rate period expire, equating to around seventy thousand loans, with a similar amount rolling off.

Chart 1: Share of bank PDH mortgage loans by interest rate type

So far, despite the magnitude of the increase in our policy rate, borrowers who have rolled off fixed rate contracts have managed to avoid substantial increases in their repayments. In 2023H1, most bank borrowers experiencing fixed rate expirations chose to re-fix with the same lender (Table 1). 58 per cent of bank PDH mortgage borrowers that experienced a fixed rate expiration in 2023H1 re-fixed their loan at a higher interest rate (44 per cent), the same interest rate (10 per cent), or a lower interest rate (4 per cent). 35 per cent had their loan roll onto an SVR, which was usually higher than the expired fixed rate. 7 per cent of these loan contracts ceased, likely indicating a switch to another lender or perhaps in some cases the full repayment of the loan.

Table 1: Share of bank PDH loans experiencing fixed rate expirations by outcome

| 2022 H1 | 2022 H2 | 2023 H1 |

|---|

| Re-fix, higher rate | 10% | 24% | 44% |

| To variable, higher rate | 26% | 16% | 34% |

| Re-fix, same rate | 23% | 16% | 10% |

| Contract ceases (e.g., switch to new lender) | 7% | 12% | 7% |

| Re-fix, lower rate | 31% | 29% | 4% |

| To variable, same or lower rate | 3% | 3% | 1% |

Source: Central Bank of Ireland

The lag between ECB policy rate increases in July 2022 and non-tracker retail bank interest rate increases in early 2023 provided a window of opportunity for some borrowers to re-fix at relatively favourable rates. Reflecting this, the typical increase in repayments during 2023H1 was relatively modest. The average increase in repayments for those rolling off fixed rates was 5 per cent, while the vast majority experienced increases of less than 10 per cent. This should not breed complacency: we expect to see further delayed pass-through of monetary policy decisions by lenders and we will continue to analyse the effects of this on all borrowers.

Household financial resilience: are we seeing signs of increased financial distress?

The Irish household sector has become more resilient, having deleveraged for over a decade prior to recent rises in interest rates. Consequently, the debt service burden of households entered this period at a relatively healthy level and provided borrowers with room to adjust to higher consumer expenditure and debt repayments.

We know that household borrowers with the highest debt service burdens tend to have lower incomes. In the context of higher consumer cost inflation and rising borrowing costs, lower income and high debt-service borrowers are a source of vulnerability in the household sector. Reasonable living expenses can only be reduced so much, while interest rate rises can quickly erode disposable income given the high debt burden.

Arrears can be a lagging indicator which is why, over the past year – as the interest rate environment changed rapidly – we have been particularly focused on ensuring that the financial sector is ready to respond to borrowers who find themselves in a difficult financial position in a consumer-focused manner.

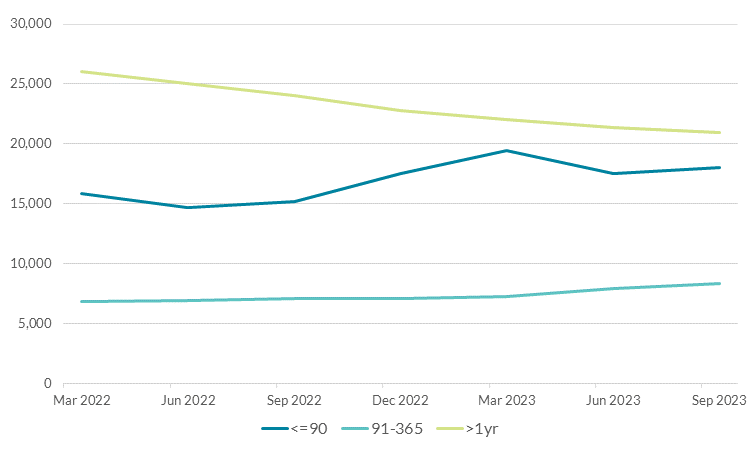

We are seeing that the number of PDH mortgage accounts in arrears was broadly stable in the year to September 2023 (Chart 2). 47,325 accounts were in arrears, which represents 6.7 per cent of all PDH mortgage accounts. Of this total, 20,022 (42 per cent) were accounts at banks and 27,303 (58 per cent) were accounts at non-banks.

Chart 2: Count of PDH mortgages in arrears by lender type

The broadly stable arrears trend in 2023 masks some movement in the depth of distress: long-term arrears cases, a scarring legacy of the previous crisis, continue their long-term decline, while early arrears cases and those missing three payments (but not yet in long-term arrears) both increased by an offsetting amount. (Chart 3)

Though every case represents a person or household in distress, when compared to historical levels, the household sector continues to appear resilient at a systemic level. Tracker rate borrowers, and in particular those with a history of previous repayment challenges dating back to the global financial crisis, appear to explain the modest rise in early arrears cases in bank loan portfolios seen up to the middle of last year.

Chart 3: Count of PDH mortgages in arrears by time in arrears

Factors that might explain this include that tracker borrowers, having experienced lower interest costs on their mortgages than other borrowers for over a decade leading to 2022, faced a larger cumulative rise in interest rates than SVR or fixed rate bank borrowers by June 2023. An important determinant of their sensitivity to higher interest rates may be whether their better monthly cash flow situation during the period of low rates was used to build up financial buffers like savings.

We are also working with others to reduce the number of accounts in long-term mortgage arrears (LTMA). From our engagement with firms on LTMA, we are continuing to see progress. In total, over 10,000 accounts have been removed from LTMA over the past 3 years. Over the year to September 2023, a further 13 per cent reduction was recorded in the number of accounts in LTMA (although, of course, challenges remain).

Conclusion – protecting the consumer

We have confidence in our consumer protection framework which is one of the most comprehensive in the EU. We have, and will continue to, engage extensively with firms to ensure they are fulfilling their obligations and protecting consumers during this period. There has been significant engagement across the system, including firms enhancing their early warning indicators and customer engagement, widening the suite of alternative repayment arrangements they offer and new support measures for borrowers in the BPFI’s “Dealing with Debt” campaign. This has introduced system-wide initiatives to support mortgage switching for the first time and increased coordination with MABS and mortgage brokers to enhance how the mortgage market operates for consumers.

I am acutely aware that some borrowers are potentially facing difficulties in meeting repayments on their mortgage. Our consumer protection framework applies irrespective of whether a loan is held by a bank or a non-bank. The Code of Conduct on Mortgage Arrears (CCMA) provides protections for both borrowers in arrears as well as those facing a prospect of arrears (‘pre-arrears’), be that due to interest rate increases or other factors, such as an increase in the cost of living. Lenders and servicers must be able to anticipate and identify cases of pre-arrears and draw up and implement procedures for dealing with borrowers, including offering alternative repayment arrangements.

Our measures seek to ensure that lenders are transparent and fair in all their dealings with borrowers and that borrowers are protected from the beginning to the end of the mortgage life cycle (for example through the initial marketing/advertising stage and in assessing the affordability and suitability of the mortgage). Effective, high quality implementation of CCMA and related protections for distressed borrowers, contributes to ongoing access to appropriate and sustainable restructuring solutions for borrowers experiencing financial distress.

I encourage anyone who believes they are at risk of falling into arrears on their mortgage payments to contact their lender/servicer. They are obliged to support you in assessing your financial position and, where necessary, identifying an appropriate and sustainable solution to any case of arrears or potential arrears. We at the Central Bank will continue to ensure firms meet their responsibilities.

Gabriel Makhlouf

References

Adhikari, Tamanna and Fang Yao, 2023, Household resilience to expenditure and debt service channels under current inflationary conditions, Financial Stability Note No. 3, Central Bank of Ireland (PDF 704.63KB).

Byrne, David, Fergal McCann, and Edward Gaffney, 2023, The interest rate exposure of mortgaged Irish households, Financial Stability Note No. 2, Central Bank of Ireland (PDF 614.49KB).

Cassidy, Jean and Cecilia Sarchi, 2023, Non-bank mortgage lending: A look into the interest rate distribution, Behind the Data, Central Bank of Ireland.

Shaikh, Sameer, Paul Kilgarriff, and Edward Gaffney, 2023, Exploring missed mortgage payments in the first year of monetary tightening, Financial Stability Note No. 9, Central Bank of Ireland (PDF 308.05KB).