Behind the Data

Understanding the Carbon Intensity of Ireland’s Financial Sectors' Securities Holdings

Bernard Kennedy and Jenny Quinn *

November 2023

This Behind the Data (BTD) presents initial estimates of carbon intensity within security holdings for the financial sector in Ireland, by institutional sub-sector. Results are broadly comparable to the euro area with some sub-sectoral differences and some evidence of concentrated exposures within Irish resident banks. Such indicators will benefit from methodological improvements and enhanced emissions disclosures over time.

The increased incidence of extreme weather events and necessary transition policies to achieve net zero emissions within the globally agreed timeframe as at late-2023 means that the financial sector’s exposure to climate-related and environmental risks is now a supervisory priority for both the Central bank of Ireland and the ECB (Donnery, 2023). As a step in addressing data gaps, the ECB as well as National Central Banks (NCBs) such as the Central Bank of Ireland have approximated transition risks – defined by Lane (2019) as the risk of a loss of capital and drop in asset prices associated with the transition to a carbon neutral economy – for financial institutions resident across the euro area.

This Behind the Data (BTD) presents the Irish results for one metric of transition risk, namely weighted average carbon intensity of the resident financial sector’s securities exposure to Non-Financial Corporations (NFCs). Such measures approximate the exposure of portfolios to carbon-intensive counterparties and therefore potential future vulnerability to transition risk. These are initial estimates, however, given data coverage issues and other caveats but should support the bridging of data gaps in this area.

In this BTD, we first explain how this measure of transition risk is calculated, including the granular data model for Irish resident financial firms, before providing initial insights into the aggregate results by financial sub-sector. The BTD therefore expands on the country level and euro area aggregate results published in January 2023 by the ECB, which also consider estimates of physical risk exposures and sustainable finance experimental statistics. These estimates of transition risks are published as analytical indicators rather than official statistics to denote their developmental nature. DeNederlandscheBank provide an overview of the limitations inherent in the current figures including the fact that the indicators only encompass a portion of financial institutions’ investment portfolios. Since the current indicators of transition risks were published in January 2023, work has commenced on a revised set of indicators of transition risks encompassing substantial methodological improvements and enhanced climate disclosures. These revised indicators of transition risks will better assess the impact of climate related risks on the financial sector and are likely to be published in the future. However, the revised indicators may differ substantially from the current indicators. Consequently, care needs to be taken when making policy inferences based on the current set of results.

This statistical and analytical project is in line with the Central Bank’s broader plans on addressing climate-related risks. Some recent Central Bank publications explaining the implications of climate change for both the financial sector as well as the formulation of policy are Lane (2019), McInerney (2022) and Carroll (2022). Most recently, Lambert et al, 2023, Adhikari et al 2023 and O’Connell, et al (2023) examine activities in the green lending market in Ireland. The Central Bank of Ireland’s new Climate Observatory provides an overview of climate-aligned financial metrics using a combination of internal and external data sources.

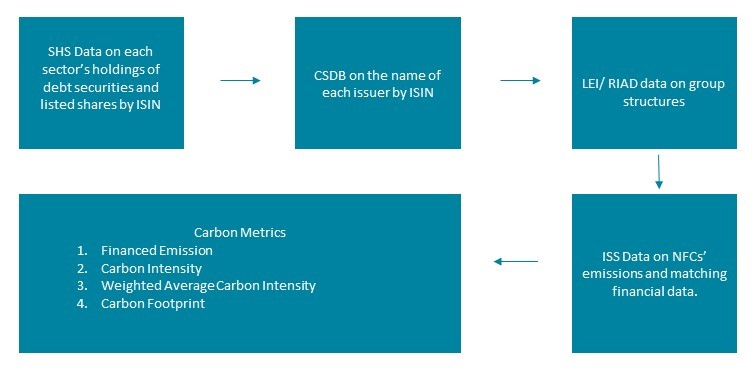

How different datasets are combined to calculate the carbon intensity of security holdings

To estimate the carbon intensity of financial institutions’ claims on NFCs’ securities, euro system granular databases were combined and this is depicted in Figure 1. The first set of datasets examined were the Securities Holdings Statistics (SHS) database and the Centralised Securities Database (CSDB) which collect data on financial institutions’ direct holdings of debt and equity securities and the issuance of debt and equity securities across the euro area. Crucially, each security has a unique identifier known as its International Standard Identification Number (ISIN). By joining the SHSS and CSDB by ISIN, it is possible to disaggregate each financial sector’s holdings of debt securities and listed shares issued by NFCs to the underlying financial firm. To distinguish each NFC, the Euro system’s master database, the Register of Institutions and Affiliates Data (RIAD) provided guidance on NFCs’ group structure incorporating within this the global standard Legal Entity identifier (LEI).

The Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) framework, which came into effect in 2014, requires the largest NFCs operating across the euro area to disclose certain non-financial information including emissions data. To comply with the directive, group-level unconsolidated data on gross Scope 1 and Scope 2 greenhouse gas emissions, which represent firms’ direct and indirect emissions respectively, are now reported by many of the larger NFCs operating across the euro area on an annual basis. To interpret the results from these different datasets, it’s necessary to apply internationally agreed metrics of carbon intensity. The purpose of such metrics is to understand better the concentrations of carbon-related assets in the financial sector and the financial system’s exposures to climate-related risks. Data on firms’ Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions along with the corresponding financial data was sourced from the Institutional Shareholder Services Group (ISS), which provides data, market intelligence, and fund services for investors, analysts, and corporations.

Figure 1: Datasets combined to calculate measures of carbon intensity across the financial sector

Estimates of carbon intensity can be compared across time and across sector

In 2017, the Task Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosures – an industry led task force supported by the Financial Stability Board – launched four new indicators intended to measure the carbon intensity of financial institutions’ claims: Financed Emissions, Carbon Intensity, Weighted Average Carbon Intensity (WACI), and Carbon Footprint. WACI has emerged as the preferred relative metric and expresses a portfolio’s exposure to carbon-intensive companies in tons of CO2 emissions per million euro (CO2e/€M). However, no consensus has emerged on the risks associated with a particular level of WACI. Consequently, the measure of WACI can only be compared across sectors at a point-in-time or across the same sectors over time.

WACI combines data on NFCs’ Scope 1 emissions with investment, portfolio value, and revenue. Investment corresponds to the value of a financial institution’s holdings of NFC debt or equity. Portfolio value typically refers to a financial institution’s total claims on NFCs for the firms included in the calculations and is used to normalize the data. The inclusion of revenue allows users to gauge how efficiently a company is able to undertake production relative to their emissions.

How do the metrics of carbon intensity compare for financial institutions resident in Ireland and the euro area?

Chart 1 displays the measure of WACI for financial institutions resident in Ireland and the euro area at end-2019 and end-2020. For 2019 and 2020, the estimated figures for banks and other financial sectors resident in Ireland results were broadly comparable with those of the euro area. Also, in line with the euro area results, the metrics for Ireland indicate that banks’ holdings of NFCs’ securities and listed shares have a higher carbon intensity compared with other resident financial sectors. Bank level data shows that for Irish resident banks’ – both internationally focused banks and retail banks - transition risks are concentrated in both a small number of corporates and a small number of securities and this concentration by individual security is depicted in Chart 2. However, the value of Irish resident banks’ holdings of NFC securities is small relative to their total holdings of securities and this makes the WACI indicator sensitive to outliers.

The analytical indicators calculate the exposure to transition risks for financial institutions resident across the euro area but the underlying securities examined include issuing NFCs resident inside and outside the euro area. Amongst financial institutions resident in Ireland, the majority of these securities considered are denominated in foreign currency reflecting the highly globalised nature of the financial sector resident in Ireland. Furthermore, only a very small portion of these claims relate to NFCs resident in Ireland reflecting the predominance of smaller NFCs in Ireland.

Chart 1: Measures of WACI for financial sub-sectors in the euro area and Ireland at end-2020

Source: European Central Bank and author’s calculations.

Note: The data in Chart 1 refer to Scope 1 emissions only. The charts are based on financial institution’s holdings of debt securities and listed shares issued by NFCs.

As outlined by the ECB in 2023, indicators such as WACI are a work in progress and carry a number of caveats such as limited data coverage across some sectors as well as compositional changes across both time and regions. Consequently, the findings presented should be evaluated while considering the limitations related to methodology and data, such as limited data coverage (and thus compositional changes) across both time and regions. For both the euro area and Ireland, the majority of securities examined are denominated in foreign currency. At present, it is not possible to separate out the impact of exchange rate changes and inflation on the different measures of transition risks. However, the revised measures of transition risk will correct for this as part of a series of methodological improvements, including where possible data greater data coverage to support end-users of these metrics.

Chart 2: Concentration of transition risks for banks resident in Ireland at end-2020

Source: European Central Bank and author’s calculations.

Note: The data in Chart 1 show the contribution of a selection of ISINs towards the reported measure of WACI for Scope 1 emissions of banks resident in Ireland at end-2020. The charts are based on banks’ holdings of debt securities and listed shares issued by NFCs. Furthermore, banks’ security holdings are typically a fraction of their loan exposures.

Conclusion

Given the importance of understanding the exposures of the financial system to climate related risks, and developments in sustainable finance, the ECB and NCBs are working to produce new data and insights relevant to these issues. The Central Bank of Ireland’s new Climate Observatory provides an overview of climate-aligned financial metrics using a combination of internal and external data sources.

To estimate the exposure of the financial sector to transition risks, the ECB in conjunction with National Central Banks including the Central Bank of Ireland have prepared analytical indicators calculating the carbon intensity of securities portfolios by institutional sector, amongst other indicators. This BTD discusses the initial Irish results and underlying granular data model for one of these metrics for 2019 and 2020. Future releases of these indicators will benefit from new data, planned methodological refinements and in time, enhanced climate emissions disclosures.

*Email [email protected] if you have any comments or questions on this note. Comments from Robert Kelly, Yvonne McCarthy, Jean Cassidy, David Duignan, Maria Woods, Tiernan Heffernan, Simone Saupe, Justin Dijk, Calogero Brancatelli, Vanessa-Maria Scharler, Andrew Kanutin and many other colleagues are gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed in this note are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Central Bank of Ireland or the ESCB.

See also: